علوم اعصاب پروس؛ سیستم حسی-پیکری: حس لامسه و حس عمقی

دعای مطالعه [ نمایش ]

بِسْمِ الله الرَّحْمنِ الرَّحیمِ

اَللّهُمَّ اَخْرِجْنى مِنْ ظُلُماتِ الْوَهْمِ

خدايا مرا بيرون آور از تاريكىهاى وهم،

وَ اَكْرِمْنى بِنُورِ الْفَهْمِ

و به نور فهم گرامى ام بدار،

اَللّهُمَّ افْتَحْ عَلَيْنا اَبْوابَ رَحْمَتِكَ

خدايا درهاى رحمتت را به روى ما بگشا،

وَانْشُرْ عَلَيْنا خَزائِنَ عُلُومِكَ بِرَحْمَتِكَ يا اَرْحَمَ الرّاحِمينَ

و خزانههاى علومت را بر ما باز كن به امید رحمتت اى مهربانترين مهربانان.

کتاب «علوم اعصاب» اثر پروس و همکاران بهعنوان یکی از جامعترین و معتبرترین منابع در حوزه علوم اعصاب، همچنان مرجع کلیدی برای درک پیچیدگیهای مغز و سیستم عصبی است. این اثر با بهرهگیری از تازهترین پژوهشها و توضیحات دقیق درباره سازوکارهای عصبی، پلی میان دانش پایه علوم اعصاب و کاربردهای بالینی ایجاد میکند و نقشی بیبدیل در آموزش، پژوهش و ارتقای دانش مغز و اعصاب ایفا مینماید.

ترجمه دقیق و علمی این شاهکار توسط برند علمی «آیندهنگاران مغز» به مدیریت داریوش طاهری، دسترسی فارسیزبانان به مرزهای نوین دانش علوم اعصاب را ممکن ساخته و رسالتی علمی برای ارتقای آموزش، فهم عمیقتر عملکرد مغز و سیستم عصبی و توسعه روشهای نوین در حوزه سلامت عصبی فراهم آورده است.

» کتاب علوم اعصاب پروس

» » فصل ۹: سیستم حسی-پیکری: حس لامسه و حس عمقی

» Neuroscience

»» Chapter 9: The Somatosensory System: Touch and Proprioception

در حال ویرایش

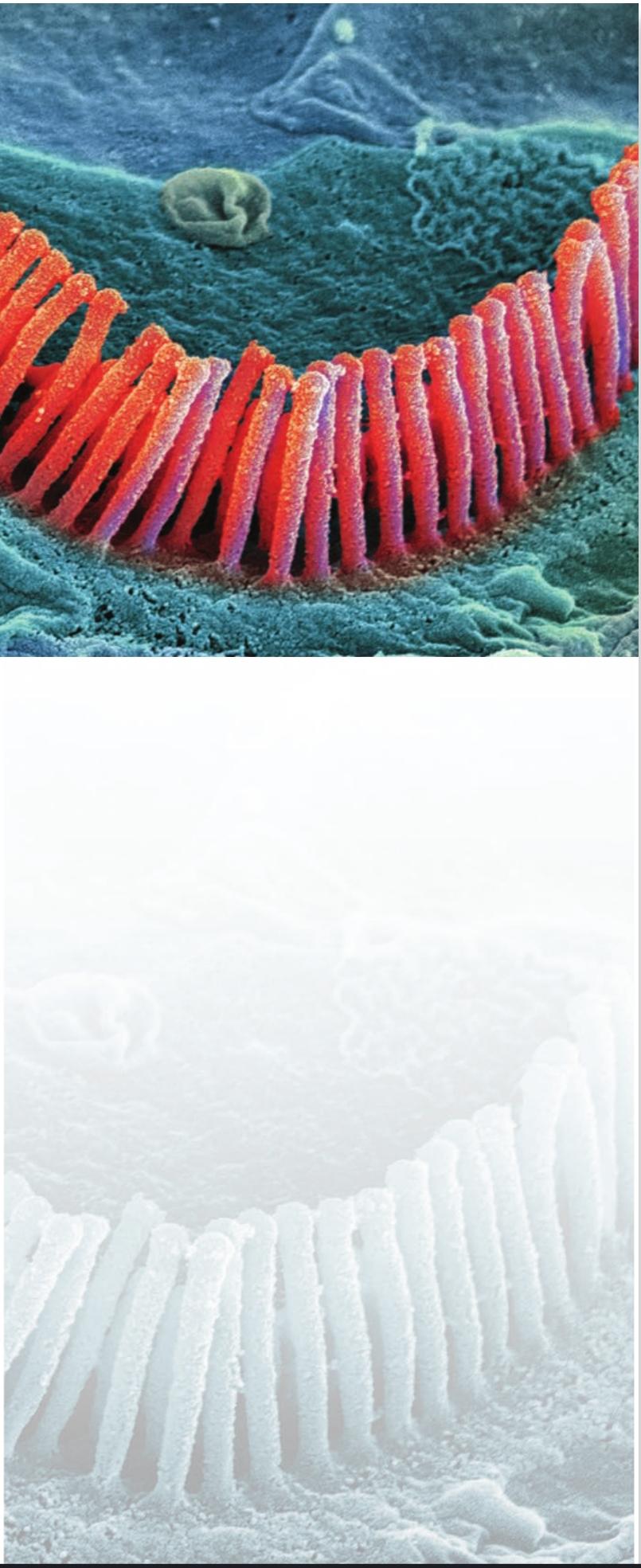

Scanning electron micrograph of outer hair cells (stereocilia) in the inner ear. Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library.

Scanning electron micrograph of outer hair cells (stereocilia) in the inner ear. Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library.

تصویر میکروسکوپ الکترونی روبشی از سلولهای مویی خارجی (استریوسیلیا) در گوش داخلی. استیو گشمایسنر/کتابخانه عکس علمی.

UNIT II

واحد دوم

Sensation and Sensory Processing

احساس و پردازش حسی

CHAPTER 9 : The Somatosensory System: Touch and Proprioception

CHAPTER 10 : Pain

CHAPTER 11 : Vision: The Eye

CHAPTER 12 : Central Visual Pathways

CHAPTER 13 : The Auditory System

CHAPTER 14 : The Vestibular System

CHAPTER 15 : The Chemical Senses

فصل ۹: سیستم حسی-پیکری: حس لامسه و حس عمقی

فصل ۱۰: درد

فصل ۱۱: بینایی چشم

فصل ۱۲: مسیرهای بینایی مرکزی

فصل ۱۳: سیستم شنوایی

فصل ۱۴: سیستم دهلیزی

فصل ۱۵: حواس شیمیایی

SENSATION ENTAILS THE ABILITY to transduce, encode, and ultimately perceive information generated by stimuli arising from both the external and internal environments. Much of the brain is devoted to these tasks. Although the basic senses somatic sensation, vision, audition, vestibular sensation, and the chemical senses are very different from one another, a few fundamental rules govern the way the nervous system deals with each of these diverse modalities. Highly specialized nerve cells called receptors convert the energy associated with mechanical forces, light, and sound waves and the presence of odorant molecules or ingested chemicals into neural signals that convey Information about stimuli (afferent sensory signals) to the spinal cord and brain. Afferent sensory signals activate central neurons capable of representing both the qualItative and quantitative aspects of the stimulus (what it is and how strong it is) and, in some modalities (somatic sensation, vision, and audition) the location of the stimulus in space (where it is).

احساس مستلزم توانایی انتقال، رمزگذاری و در نهایت درک اطلاعات تولید شده توسط محرکهای ناشی از محیطهای خارجی و داخلی است. بخش زیادی از مغز به این وظایف اختصاص داده شده است. اگرچه حواس پایه – حس پیکری، بینایی، شنوایی، حس دهلیزی و حواس شیمیایی – بسیار متفاوت از یکدیگر هستند، اما چند قانون اساسی نحوه برخورد سیستم عصبی با هر یک از این حالتهای متنوع را کنترل میکند. سلولهای عصبی بسیار تخصصی به نام گیرندهها، انرژی مرتبط با نیروهای مکانیکی، امواج نور و صدا و وجود مولکولهای بو یا مواد شیمیایی بلعیده شده را به سیگنالهای عصبی تبدیل میکنند که اطلاعات مربوط به محرکها (سیگنالهای حسی آوران) را به نخاع و مغز منتقل میکنند. سیگنالهای حسی آوران، نورونهای مرکزی را فعال میکنند که قادر به نمایش جنبههای کیفی و کمی محرک (چه چیزی و چقدر قوی است) و در برخی از حالتها (حس پیکری، بینایی و شنوایی) مکان محرک در فضا (جایی که هست) هستند.

The clinical evaluation of patients routinely requires an assessment of the sensory systems to infer the nature and location of potential neurological problems. Knowledge of where and how the different sensory modalities are transduced, relayed, represented, and further processed to generate appropriate behavioral responses is therefore essential to understanding and treating a wide variety of diseases. Accordingly, these chapters on the neurobiology of sensation also introduce some of the major structure/function relationships in the sensory components of the nervous system.

ارزیابی بالینی بیماران به طور معمول نیازمند ارزیابی سیستمهای حسی برای پی بردن به ماهیت و محل مشکلات عصبی بالقوه است. بنابراین، آگاهی از محل و چگونگی انتقال، انتقال، نمایش و پردازش بیشتر روشهای مختلف حسی برای ایجاد پاسخهای رفتاری مناسب، برای درک و درمان طیف گستردهای از بیماریها ضروری است. بر این اساس، این فصلها در مورد نوروبیولوژی حس، برخی از روابط اصلی ساختار/عملکرد را در اجزای حسی سیستم عصبی نیز معرفی میکنند.

Overview

THE SOMATOSENSORY SYSTEM is arguably the most diverse of the sensory systems, mediating a range of sensations-touch, pressure, vibration, limb position, heat, cold, itch, and pain that are transduced by receptors within the skin, muscles, or joints and conveyed to a variety of CNS targets. Not surprisingly, this complex neurobiological machinery can be divided into functionally distinct subsystems with distinct sets of peripheral receptors and central pathways. One subsystem transmits information from cutaneous mechanoreceptors and mediates the sensations of fine touch, vibration, and pressure. Another originates in specialized receptors that are associated with muscles, tendons, and joints and is responsible for proprioception our ability to sense the position of our own limbs and other body parts in space. A third subsystem arises from receptors that supply information about painful stimuli and changes in temperature as well as nondiscriminative (or sensual) touch. This chapter focuses on the tactile and proprioceptive subsystems; the mechanisms responsible for sensations of pain, temperature, and coarse sensual touch are considered in the following chapter.

مرور کلی

سیستم حسی-پیکری مسلماً متنوعترین سیستم حسی است که طیف وسیعی از احساسات – لمس، فشار، لرزش، موقعیت اندام، گرما، سرما، خارش و درد – را که توسط گیرندههای درون پوست، عضلات یا مفاصل منتقل شده و به اهداف مختلف CNS منتقل میشوند، واسطهگری میکند. جای تعجب نیست که این دستگاه عصبی-زیستی پیچیده را میتوان به زیرسیستمهای عملکردی متمایز با مجموعههای متمایزی از گیرندههای محیطی و مسیرهای مرکزی تقسیم کرد. یک زیرسیستم اطلاعات را از گیرندههای مکانیکی پوستی منتقل میکند و واسطه احساسات لمس ظریف، لرزش و فشار است. دیگری از گیرندههای تخصصی سرچشمه میگیرد که با عضلات، تاندونها و مفاصل مرتبط هستند و مسئول حس عمقی هستند – توانایی ما در حس موقعیت اندامهای خود و سایر قسمتهای بدن در فضا. زیرسیستم سوم از گیرندههایی ناشی میشود که اطلاعات مربوط به محرکهای دردناک و تغییرات دما و همچنین لمس غیرتمایزی (یا حسی) را ارائه میدهند. این فصل بر زیرسیستمهای لمسی و حس عمقی تمرکز دارد. مکانیسمهای مسئول احساس درد، دما و لمس شهوانی خشن در فصل بعد مورد بررسی قرار میگیرند.

Afferent Fibers Convey Somatosensory Information to the Central Nervous System

Somatic sensation originates from the activity of afferent nerve fibers whose peripheral processes ramify within the skin, muscles, or joints (Figure 9.1A). The cell bodies of afferent fibers reside in a series of ganglia that lie alongside the spinal cord and the brainstem and are considered part of the peripheral nervous system. Neurons in the dorsal root ganglia and in the cranial nerve ganglia (for the body and head, respectively) are the critical links supplying CNS circuits with information about sensory events that occur in the periphery.

فیبرهای آوران اطلاعات حسی-پیکری را به سیستم عصبی مرکزی منتقل میکنند

حس پیکری از فعالیت فیبرهای عصبی آوران که فرآیندهای محیطی آنها در پوست، عضلات یا مفاصل منشعب میشود، سرچشمه میگیرد (شکل 9.1A). جسم سلولی فیبرهای آوران در مجموعهای از گانگلیونها قرار دارند که در کنار نخاع و ساقه مغز قرار دارند و بخشی از سیستم عصبی محیطی محسوب میشوند. نورونهای موجود در گانگلیونهای ریشه پشتی و در گانگلیونهای عصب جمجمهای (به ترتیب برای بدن و سر) حلقههای حیاتی هستند که اطلاعات مربوط به رویدادهای حسی که در محیط رخ میدهند را به مدارهای سیستم عصبی مرکزی (CNS) ارائه میدهند.

Action potentials generated in afferent fibers by events that occur in the skin, muscles or joints propagate along the fibers and past the locations of the cell bodies in the ganglia until they reach a variety of targets in the CNS (Figure 9.1B). Peripheral and central components of afferent fibers are continuous, attached to the cell body in the ganglia by a single process. For this reason, neurons in the dorsal root ganglia are often called pseudounipolar. Because of this configuration, conduction of electrical activity through the membrane of the cell body is not an obligatory step in conveying sensory information to central targets. Nevertheless, cell bodies of sensory afferents play a critical role in maintaining the cellular machinery that mediates transduction, conduction, and transmission by sensory afferent fibers.

پتانسیلهای عمل تولید شده در فیبرهای آوران توسط رویدادهایی که در پوست، عضلات یا مفاصل رخ میدهند، در امتداد فیبرها و از محلهای جسم سلولی در گانگلیونها عبور میکنند تا زمانی که به اهداف مختلفی در سیستم عصبی مرکزی برسند (شکل 9.1B). اجزای محیطی و مرکزی فیبرهای آوران پیوسته هستند و توسط یک فرآیند واحد به جسم سلولی در گانگلیونها متصل میشوند. به همین دلیل، نورونهای موجود در گانگلیونهای ریشه پشتی اغلب شبه تک قطبی نامیده میشوند. به دلیل این پیکربندی، هدایت فعالیت الکتریکی از طریق غشای جسم سلولی گامی اجباری در انتقال اطلاعات حسی به اهداف مرکزی نیست. با این وجود، اجسام سلولی آورانهای حسی نقش مهمی در حفظ ماشینآلات سلولی دارند که واسطه انتقال، هدایت و انتقال توسط فیبرهای آوران حسی هستند.

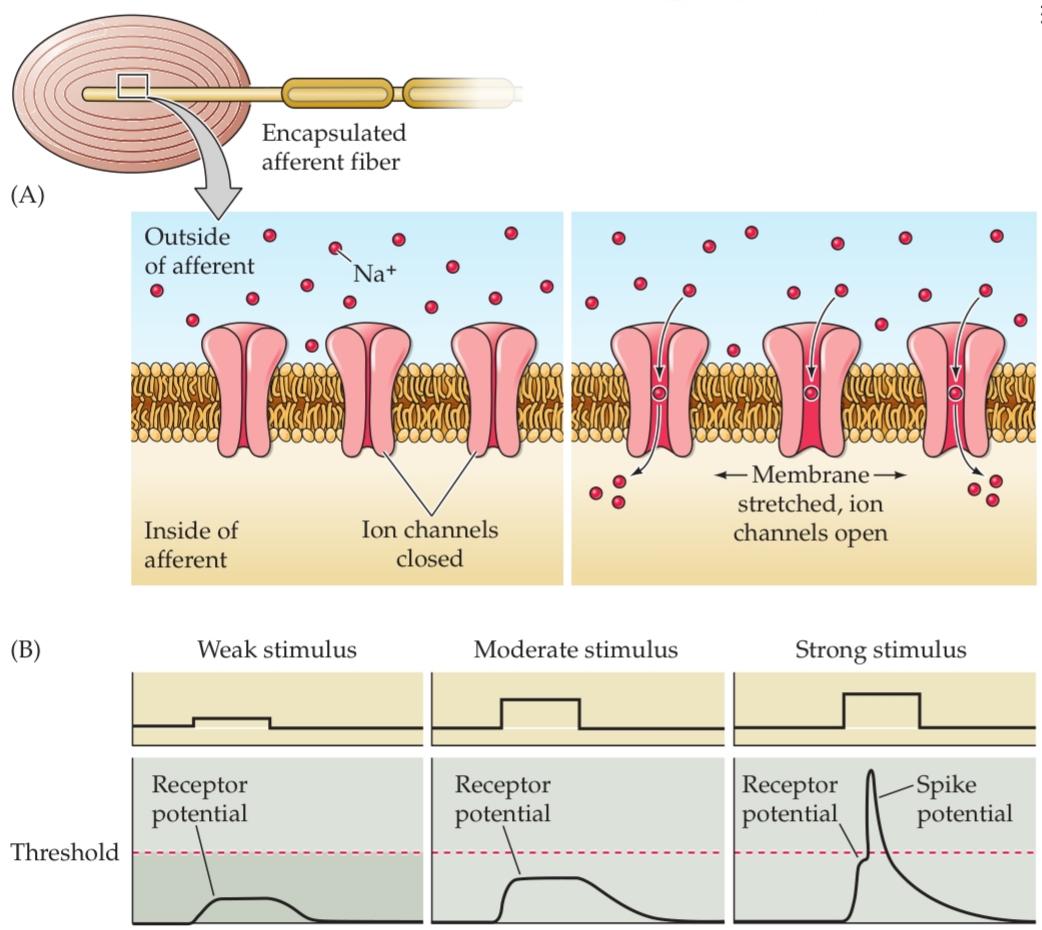

The fundamental mechanism of sensory transduction the process of converting the energy of a stimulus into an electrical signal is similar in all somatosensory afferents: A stimulus alters the permeability of cation channels in the afferent nerve endings, generating a depolarizing current known as a receptor (or generator) potential (Figure 9.2). If sufficient in magnitude, the receptor potential reaches threshold for the generation of action potentials in the afferent fiber; the resulting rate of action potential firing is roughly proportional to the magnitude of the depolarization, as described in Chapters 2 and 3. Recently, the first family of mammalian mechanotransduction channels was identified. It consists of two members: Piezol and Piezo2 (Greek piesi, “pressure”; see Chapter 4). Piezo channels are predicted to have more than 30 transmembrane domains. Purified Piezo proteins reconstituted in artificial lipid bilayers form ion channels that transduce tension in the surrounding membrane. Importantly, Piezo2 is expressed in subsets of sensory afferent neurons as well as in other cells.

مکانیسم اساسی انتقال حسی فرآیند تبدیل انرژی یک محرک به یک سیگنال الکتریکی در تمام آورانهای حسی-پیکری مشابه است: یک محرک، نفوذپذیری کانالهای کاتیونی را در انتهای عصب آوران تغییر میدهد و یک جریان دپلاریزه کننده به نام پتانسیل گیرنده (یا مولد) ایجاد میکند (شکل 9.2). اگر مقدار آن کافی باشد، پتانسیل گیرنده به آستانه تولید پتانسیلهای عمل در فیبر آوران میرسد. سرعت شلیک پتانسیل عمل حاصل تقریباً متناسب با مقدار دپلاریزاسیون است، همانطور که در فصلهای 2 و 3 توضیح داده شده است. اخیراً، اولین خانواده از کانالهای انتقال مکانیکی پستانداران شناسایی شده است. این خانواده از دو عضو تشکیل شده است: پیزول و پیزو2 (به یونانی piesi، “فشار”؛ به فصل 4 مراجعه کنید). پیشبینی میشود کانالهای پیزو بیش از 30 دامنه غشایی داشته باشند. پروتئینهای پیزو خالص شده که در دولایههای لیپیدی مصنوعی بازسازی شدهاند، کانالهای یونی را تشکیل میدهند که تنش را در غشای اطراف منتقل میکنند. نکته مهم این است که Piezo2 در زیرمجموعههایی از نورونهای آوران حسی و همچنین در سایر سلولها بیان میشود.

FIGURE 9.1 Somatosensory afferents convey information from the skin surface to central circuits. (A) The cell bodies of somatosensory afferent fibers conveying information about the body reside in a series of dorsal root ganglia that lie along the spinal cord; those conveying information about the head are found primarily in the trigeminal ganglia. (B) Pseudounipolar neurons in the dorsal root ganglia give rise to peripheral processes that ramify within the skin (or muscles or joints) and central processes that synapse with neurons located in the spinal cord and at higher levels of the nervous system. The peripheral processes of mechanore- ceptor afferents are encapsulated by specialized receptor cells; afferents carrying pain and temperature information terminate in the periphery as free endings.

شکل ۹.۱ آورانهای حسی-پیکری اطلاعات را از سطح پوست به مدارهای مرکزی منتقل میکنند. (الف) جسم سلولی فیبرهای آوران حسی-پیکری که اطلاعات مربوط به بدن را منتقل میکنند، در مجموعهای از گانگلیونهای ریشه پشتی قرار دارند که در امتداد نخاع قرار دارند. آنهایی که اطلاعات مربوط به سر را منتقل میکنند، عمدتاً در گانگلیونهای سه قلو یافت میشوند. (ب) نورونهای شبه تک قطبی در گانگلیونهای ریشه پشتی باعث ایجاد فرآیندهای محیطی میشوند که در پوست (یا عضلات یا مفاصل) منشعب میشوند و فرآیندهای مرکزی که با نورونهای واقع در نخاع و در سطوح بالاتر سیستم عصبی سیناپس برقرار میکنند. فرآیندهای محیطی آورانهای گیرنده مکانیکی توسط سلولهای گیرنده تخصصی محصور شدهاند. آورانهای حامل اطلاعات درد و دما در محیط به صورت انتهای آزاد خاتمه مییابند.

Afferent fiber terminals that detect and transmit touch sensory stimuli (mechanoreceptors) are often encapsulated by specialized receptor cells that help tune the afferent fiber to particular features of somatic stimulation. Afferent fibers that lack specialized receptor cells are referred to as free nerve endings and are especially important in the sensation of pain (see Chapter 10). Afferents that have encapsulated endings generally have lower thresholds for action potential generation and are thus are more sensitive to sensory stimulation than are free nerve endings.

پایانههای فیبر آوران که محرکهای حسی لمسی (گیرندههای مکانیکی) را تشخیص داده و منتقل میکنند، اغلب توسط سلولهای گیرنده تخصصی محصور شدهاند که به تنظیم فیبر آوران برای ویژگیهای خاص تحریک سوماتیک کمک میکنند. فیبرهای آوران که فاقد سلولهای گیرنده تخصصی هستند، به عنوان پایانههای عصبی آزاد شناخته میشوند و به ویژه در احساس درد اهمیت دارند (به فصل 10 مراجعه کنید). آورانهایی که پایانههای کپسولدار دارند، عموماً آستانه پایینتری برای تولید پتانسیل عمل دارند و بنابراین نسبت به پایانههای عصبی آزاد، به تحریک حسی حساستر هستند.

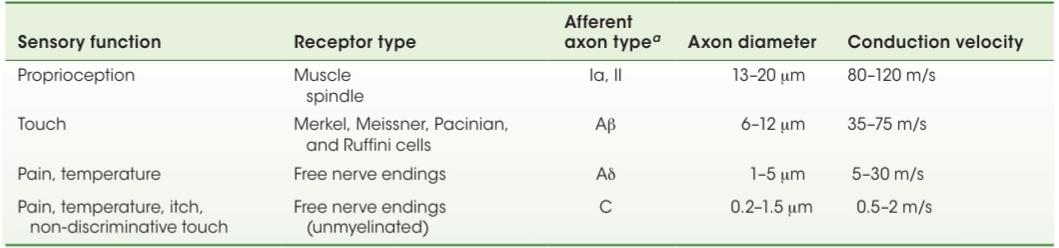

Somatosensory Afferents Convey Different Functional Information

Somatosensory afferents differ significantly in their response properties. These differences, taken together, define distinct classes of afferents, each of which makes unique contributions to somatic sensation. Axon diameter is one factor that differentiates classes of somatosensory afferents (Table 9.1). The largest diameter sensory afferents (designated Ia) are those that supply the sensory receptors in the muscles. Most of the information subserving touch is conveyed by slightly smaller diameter fibers (Aẞ afferents), and information about pain and temperature is conveyed by even smaller diameter fibers (AS and C). The diameter of the axon determines the action potential conduction speed and is well matched to the properties of the central circuits and the various behavior demands for which each type of sensory afferent is employed (see Chapter 16).

آورانهای حسی-پیکری اطلاعات عملکردی متفاوتی را منتقل میکنند

آورانهای حسی-پیکری در ویژگیهای پاسخ خود تفاوت قابل توجهی دارند. این تفاوتها، در کنار هم، دستههای متمایزی از آورانها را تعریف میکنند که هر کدام سهم منحصر به فردی در حس پیکری دارند. قطر آکسون یکی از عواملی است که دستههای آوران حسی-پیکری را متمایز میکند (جدول 9.1). آورانهای حسی با بزرگترین قطر (که با Ia مشخص شدهاند) آنهایی هستند که گیرندههای حسی را در عضلات تغذیه میکنند. بیشتر اطلاعات مربوط به لمس توسط فیبرهای با قطر کمی کوچکتر (آورانهای Aẞ) منتقل میشوند و اطلاعات مربوط به درد و دما توسط فیبرهای با قطر حتی کوچکتر (AS و C) منتقل میشوند. قطر آکسون سرعت هدایت پتانسیل عمل را تعیین میکند و به خوبی با خواص مدارهای مرکزی و خواستههای رفتاری مختلفی که هر نوع آوران حسی برای آنها به کار میرود، مطابقت دارد (به فصل 16 مراجعه کنید).

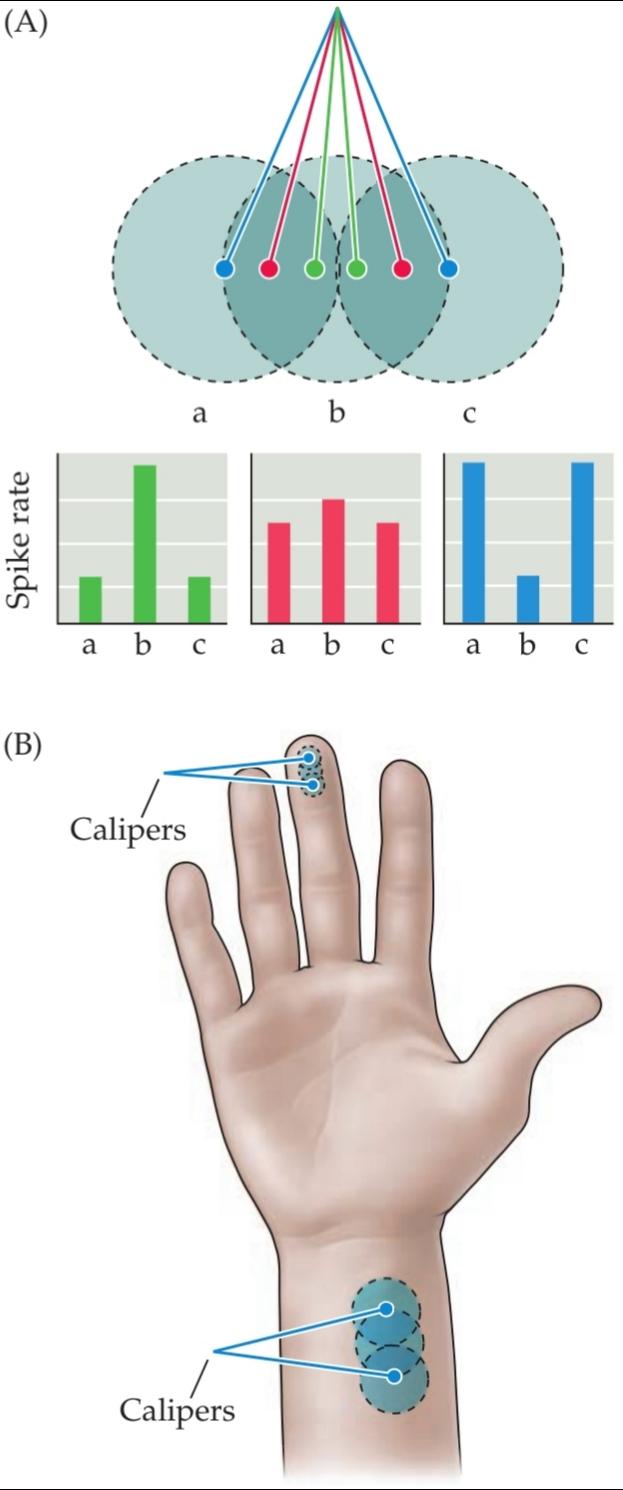

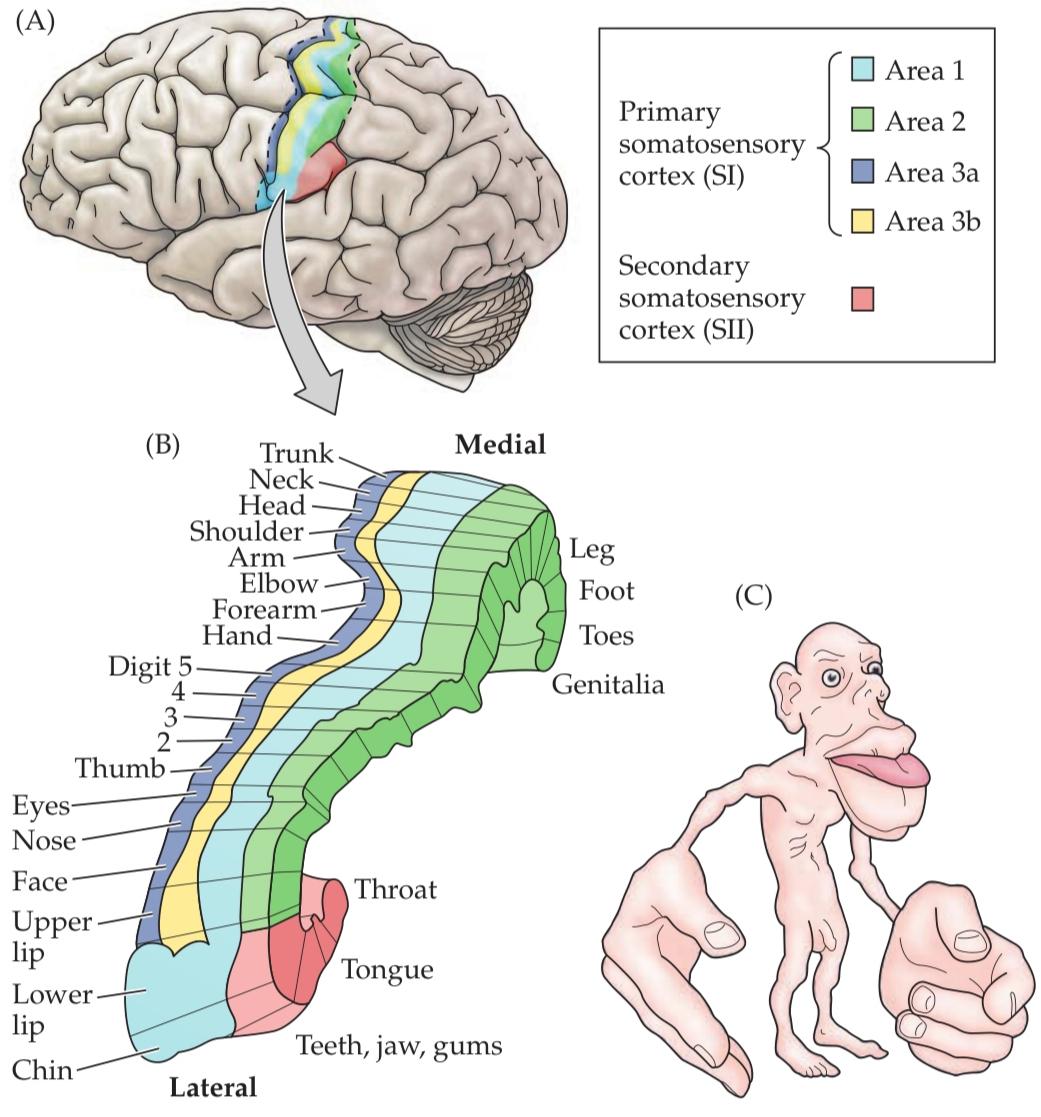

Another distinguishing feature of sensory afferents is the size of the receptive field for cutaneous afferents, the area of the skin surface over which stimulation results in a significant change in the rate of action potentials (Figure 9.3A). A given region of the body surface is served by sensory afferents that vary significantly in the size of their receptive fields. The size of the receptive field is largely a function of the branching characteristics of the afferent within the skin; smaller arborizations result in smaller receptive fields. Moreover, there are systematic regional variations in the average size of afferent receptive fields that reflect the density of afferent fibers supplying the area. The receptive fields in regions with dense innervation (fingers, lips, toes) are relatively small compared with those in the forearm or back that are innervated by a smaller number of afferent fibers (Figure 9.3B).

یکی دیگر از ویژگیهای متمایز آورانهای حسی، اندازه میدان گیرنده برای آورانهای پوستی است، ناحیهای از سطح پوست که تحریک روی آن منجر به تغییر قابل توجهی در سرعت پتانسیلهای عمل میشود (شکل 9.3A). یک ناحیه مشخص از سطح بدن توسط آورانهای حسی که اندازه میدانهای پذیرنده آنها به طور قابل توجهی متفاوت است، پوشش داده میشود. اندازه میدان گیرنده تا حد زیادی تابع ویژگیهای شاخهبندی آوران در پوست است؛ شاخهبندیهای کوچکتر منجر به میدانهای پذیرنده کوچکتر میشوند. علاوه بر این، تغییرات منطقهای سیستماتیکی در اندازه متوسط میدانهای پذیرنده آوران وجود دارد که نشان دهنده تراکم فیبرهای آوران تغذیه کننده آن ناحیه است. میدانهای پذیرنده در مناطقی با عصبدهی متراکم (انگشتان دست، لبها، انگشتان پا) در مقایسه با میدانهای پذیرنده در ساعد یا پشت که توسط تعداد کمتری از فیبرهای آوران عصبدهی میشوند، نسبتاً کوچک هستند (شکل 9.3B).

FIGURE 9.2 Transduction in a mechanosensory afferent. The process is illustrated here for a Pacinian corpuscle. (A) Deformation of the capsule leads to a stretching of the membrane of the afferent fiber, increasing the probability of opening mechanotransduction channels in the membrane. (B) Opening of these cation channels leads to depolarization of the afferent fiber (receptor potential). If the afferent is sufficiently depolarized, an action potential is generated and propagates to central targets.

شکل ۹.۲ انتقال در یک آوران حسگرهای مکانیکی. این فرآیند در اینجا برای یک جسمک پاچینی نشان داده شده است. (الف) تغییر شکل کپسول منجر به کشش غشای فیبر آوران میشود و احتمال باز شدن کانالهای انتقال مکانیکی در غشاء را افزایش میدهد. (ب) باز شدن این کانالهای کاتیونی منجر به دپلاریزاسیون فیبر آوران (پتانسیل گیرنده) میشود. اگر آوران به اندازه کافی دپلاریزه شود، یک پتانسیل عمل تولید میشود و به اهداف مرکزی منتشر میشود.

Regional differences in receptive field size and innervation density are the major factors that limit the spatial accuracy with which tactile stimuli can be sensed. Thus, measures of two point discrimination the minimum interstimulus distance required to perceive two simultaneously applied stimuli as distinct vary dramatically across the skin surface (Figure 9.3C). On the fingertips, stimuli (the indentation points produced by the tips of a caliper, for example) are perceived as distinct if they are separated by roughly 2 mm, but the same stimuli applied to the upper arm are not perceived as distinct until they are at least 40 mm apart.

تفاوتهای منطقهای در اندازه میدان گیرنده و تراکم عصبدهی، عوامل اصلی محدودکننده دقت مکانی هستند که با آن میتوان محرکهای لمسی را حس کرد. بنابراین، معیارهای تمایز دو نقطه – حداقل فاصله بین محرکهای مورد نیاز برای درک دو محرک اعمالشده همزمان به صورت مجزا – در سطح پوست به طور چشمگیری متفاوت است (شکل 9.3C). در نوک انگشتان، محرکها (به عنوان مثال، نقاط فرورفتگی ایجاد شده توسط نوک یک کولیس) اگر تقریباً 2 میلیمتر از هم فاصله داشته باشند، متمایز درک میشوند، اما همان محرکهای اعمالشده روی بازو تا زمانی که حداقل 40 میلیمتر از هم فاصله نداشته باشند، متمایز درک نمیشوند.

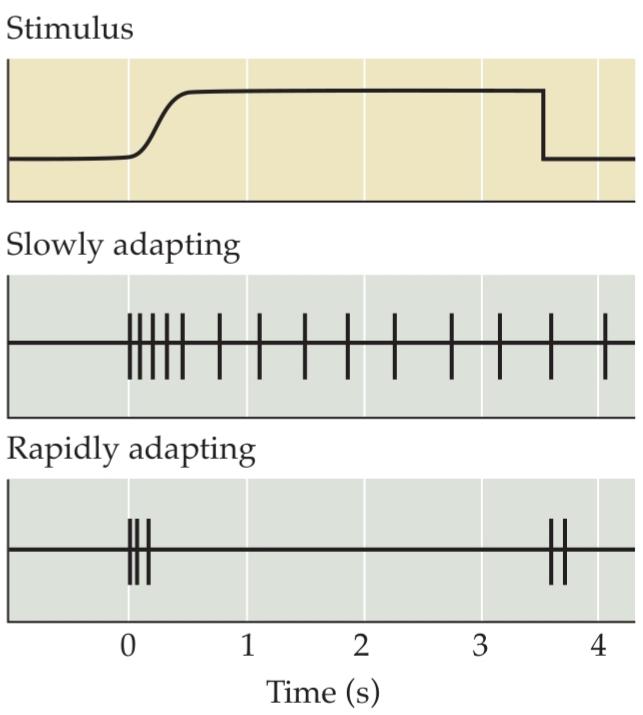

Sensory afferents are further differentiated by the temporal dynamics of their response to sensory stimulation. Some afferents fire rapidly when a stimulus is first presented, then fall silent in the presence of continued stimulation; others generate a sustained discharge in the presence of an ongoing stimulus (Figure 9.4). Rapidly adapting afferents (those that become quiescent in the face of continued stimulation) are thought to be particularly effective in conveying information about changes in ongoing stimulation such as those produced by stimulus movement. In contrast, slowly adapting afferents are better suited to provide information about the spatial attributes of the stimulus, such as size and shape. At least for some classes of afferent fibers, the adaptation characteristics are attributable to the properties of the receptor cells that encapsulate them. Rapidly adapting afferents that are associated with Pacinian corpuscles (see the following section) become slowly adapting when the corpuscle is removed.

آورانهای حسی با توجه به پویایی زمانی پاسخشان به تحریک حسی، بیشتر متمایز میشوند. برخی از آورانها هنگامی که یک محرک برای اولین بار ارائه میشود، به سرعت فعال میشوند، سپس در حضور تحریک مداوم خاموش میشوند؛ برخی دیگر در حضور یک محرک مداوم، تخلیه مداوم ایجاد میکنند (شکل 9.4). تصور میشود آورانهای با سازگاری سریع (آنهایی که در مواجهه با تحریک مداوم خاموش میشوند) به ویژه در انتقال اطلاعات در مورد تغییرات در تحریک مداوم، مانند تغییرات ایجاد شده توسط حرکت محرک، مؤثر هستند. در مقابل، آورانهایی که به آرامی سازگار میشوند، برای ارائه اطلاعات در مورد ویژگیهای مکانی محرک، مانند اندازه و شکل، مناسبتر هستند. حداقل برای برخی از دستههای فیبرهای آوران، ویژگیهای سازگاری به خواص سلولهای گیرندهای که آنها را در بر میگیرند، نسبت داده میشود. آورانهای با سازگاری سریع که با جسمکهای پاچینی مرتبط هستند (به بخش زیر مراجعه کنید) هنگامی که جسمک برداشته میشود، به آرامی سازگار میشوند.

TABLE 9.1 Somatosensory Afferents That Link Receptors to the Central Nervous System

جدول ۹.۱ آورانهای حسی-پیکری که گیرندهها را به سیستم عصبی مرکزی متصل میکنند

“During the 1920s and 1930s, there was a virtual cottage industry classifying axons according to their conduction velocity. Three main categories were discerned, called A, B, and C. A comprises the largest and fastest axons, C the smallest and slowest. Mechanoreceptor axons generally fall into category A. The A group is further broken down into subgroups designated α (the fastest), β, and δ (the slowest). To make matters even more confusing, muscle afferent axons are usually classified into four additional groups-I (the fastest), II, III, and IV (the slowest) with subgroups designated by lowercase roman letters! (After Rosenzweig et al., 2005.)

“در طول دهههای ۱۹۲۰ و ۱۹۳۰، یک صنعت خانگی مجازی وجود داشت که آکسونها را بر اساس سرعت هدایت آنها طبقهبندی میکرد. سه دسته اصلی به نامهای A، B و C تشخیص داده شدند. A شامل بزرگترین و سریعترین آکسونها و C کوچکترین و کندترین آنها است. آکسونهای گیرنده مکانیکی عموماً در دسته A قرار میگیرند. گروه A به زیرگروههای α (سریعترین)، β و δ (کندترین) تقسیم میشود. برای اینکه موضوع گیجکنندهتر شود، آکسونهای آوران عضلانی معمولاً به چهار گروه اضافی – I (سریعترین)، II، III و IV (کندترین) – طبقهبندی میشوند که زیرگروهها با حروف کوچک رومی مشخص میشوند! (به نقل از روزنزویگ و همکاران، ۲۰۰۵.)

FIGURE 9.3 Receptive fields and the two point discrimination threshold. (A) Patterns of activity in three mechanosensory afferent fibers with overlapping receptive fields a, b, and c on the skin surface. When two point discrimination stimuli are closely spaced (green dots and histogram), there is a single focus of neural activity, with afferent b firing most actively. As the stimuli are moved farther apart (red dots and histogram), the activity in afferents a and c increases and the activity in b decreases. At some separation distance (blue dots and histogram), the activity in a and c exceeds that in b to such an extent that two discrete foci of stimulation can be identified. This differential pattern of activity forms the basis for the two point discrimination threshold. Stimulation applied to the center of the receptive field tends to evoke stronger responses than stimuli applied at more eccentric locations within the receptive field (see Figure 1.14). (B) The two point discrimination threshold in the fingers is much finer than that in the wrist because of differences in the sizes of afferent receptive fields that is, the separation distance necessary to produce two distinct foci of neural activity in the population of afferents innervating the lower arm is much greater than that for the afferents innervating the fingertips. (C) Differences in the two-point discrimination threshold across the surface of the body. Somatic acuity is much higher in the fingers, toes, and face than in the arms, legs, or torso. (C after Weinstein, 1968.)

شکل ۹.۳ میدانهای پذیرنده و آستانه تمایز دو نقطهای. (الف) الگوهای فعالیت در سه فیبر آوران حسگرهای مکانیکی با میدانهای پذیرنده همپوشانی a، b و c در سطح پوست. هنگامی که محرکهای تمایز دو نقطهای از هم فاصله کمی دارند (نقاط سبز و هیستوگرام)، یک کانون فعالیت عصبی وجود دارد که در آن آوران b بیشترین فعالیت را از خود نشان میدهد. با دورتر شدن محرکها از یکدیگر (نقاط قرمز و هیستوگرام)، فعالیت در آورانهای a و c افزایش و فعالیت در b کاهش مییابد. در فاصلهای از هم جدا (نقاط آبی و هیستوگرام)، فعالیت در a و c از فعالیت در b فراتر میرود تا حدی که میتوان دو کانون مجزای تحریک را شناسایی کرد. این الگوی افتراقی فعالیت، اساس آستانه تمایز دو نقطهای را تشکیل میدهد. تحریک اعمال شده به مرکز میدان گیرنده، پاسخهای قویتری نسبت به محرکهای اعمال شده در مکانهای غیرمتعارفتر در میدان گیرنده ایجاد میکند (شکل ۱.۱۴ را ببینید). (ب) آستانه تشخیص دو نقطه در انگشتان دست بسیار کمتر از مچ دست است، به دلیل تفاوت در اندازه میدانهای پذیرنده آوران، یعنی فاصله جدایی لازم برای ایجاد دو کانون مجزا از فعالیت عصبی در جمعیت آورانهایی که ساعد را عصبدهی میکنند، بسیار بیشتر از آورانهایی است که نوک انگشتان را عصبدهی میکنند. (ج) تفاوت در آستانه تشخیص دو نقطه در سطح بدن. تیزبینی سوماتیک در انگشتان دست، پا و صورت بسیار بیشتر از بازوها، پاها یا تنه است. (ج پس از واینشتاین، ۱۹۶۸.)

Finally, sensory afferents respond differently to the qualities of somatosensory stimulation. Due to differences in the properties of the channels expressed in sensory afferents, or to the filter properties of the specialized receptor cells that encapsulate many sensory afferents, generator potentials are produced only by a restricted set of stimuli that impinge on a given afferent fiber. For example, the afferents encapsulated within specialized receptor cells in the skin respond vigorously to mechanical deformation of the skin surface, but not to changes in temperature or to the presence of mechanical forces or chemicals that are known to elicit painful sensations. The latter stimuli are especially effective in driving the responses of sensory afferents known as nociceptors (see Chapter 10) that terminate in the skin as free nerve endings. Further subtypes of mechanoreceptors and nociceptors are identified on the basis of their distinct responses to somatic stimulation.

در نهایت، آورانهای حسی به کیفیت تحریک حسی-پیکری پاسخ متفاوتی میدهند. به دلیل تفاوت در خواص کانالهای بیانشده در آورانهای حسی، یا به دلیل خواص فیلتر سلولهای گیرنده تخصصی که بسیاری از آورانهای حسی را در بر میگیرند، پتانسیلهای مولد فقط توسط مجموعهای محدود از محرکها که به یک فیبر آوران معین برخورد میکنند، تولید میشوند. به عنوان مثال، آورانهای محصور شده در سلولهای گیرنده تخصصی در پوست به شدت به تغییر شکل مکانیکی سطح پوست پاسخ میدهند، اما به تغییرات دما یا وجود نیروهای مکانیکی یا مواد شیمیایی که به عنوان ایجادکننده احساسات دردناک شناخته میشوند، پاسخ نمیدهند. محرکهای اخیر به ویژه در هدایت پاسخهای آورانهای حسی معروف به گیرندههای درد (به فصل 10 مراجعه کنید) که به عنوان پایانههای عصبی آزاد در پوست خاتمه مییابند، مؤثر هستند. زیرگروههای بیشتری از گیرندههای مکانیکی و گیرندههای درد بر اساس پاسخهای متمایز آنها به تحریک سوماتیک شناسایی میشوند.

While a given sensory afferent can give rise to multiple peripheral branches, the transduction properties of all the branches of a single fiber are identical. As a result, somatosensory afferents constitute parallel pathways that differ in conduction velocity, receptive field size, dynamics, and effective stimulus features. As will become apparent, these different pathways remain segregated through several stages of central processing, and their activity contributes in unique ways to the extraction of somatosensory information that is necessary for the appropriate control of both goaloriented and reflexive movements.

در حالی که یک آوران حسی معین میتواند شاخههای محیطی متعددی ایجاد کند، خواص انتقال تمام شاخههای یک فیبر واحد یکسان است. در نتیجه، آورانهای حسی-پیکری مسیرهای موازی تشکیل میدهند که در سرعت هدایت، اندازه میدان گیرنده، دینامیک و ویژگیهای محرک مؤثر متفاوت هستند. همانطور که آشکار خواهد شد، این مسیرهای مختلف در طول چندین مرحله از پردازش مرکزی از هم جدا میمانند و فعالیت آنها به روشهای منحصر به فردی در استخراج اطلاعات حسی-پیکری که برای کنترل مناسب حرکات هدفمند و رفلکسی ضروری است، نقش دارد.

FIGURE 9.4 Slowly and rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors provide different information. Slowly adapting receptors continue responding to a stimulus, whereas rapidly adapting receptors respond only at the onset (and often the offset) of stimulation. These functional differences allow mechanoreceptors to provide information about both the static (via slowly adapting receptors) and dynamic (via rapidly adapting receptors) qualities of a stimulus.

شکل ۹.۴ گیرندههای مکانیکی با سازگاری آهسته و سریع، اطلاعات متفاوتی ارائه میدهند. گیرندههای با سازگاری آهسته به پاسخ دادن به یک محرک ادامه میدهند، در حالی که گیرندههای با سازگاری سریع فقط در شروع (و اغلب در زمان جبران) تحریک پاسخ میدهند. این تفاوتهای عملکردی به گیرندههای مکانیکی اجازه میدهد تا اطلاعاتی در مورد ویژگیهای استاتیک (از طریق گیرندههای با سازگاری آهسته) و دینامیک (از طریق گیرندههای با سازگاری سریع) یک محرک ارائه دهند.

Mechanoreceptors Specialized to Receive Tactile Information

Our understanding of the contribution of distinct afferent pathways to cutaneous sensation is best developed for the glabrous (hairless) portions of the hand (i.e., the palm and fingertips). These regions of the skin surface are specialized to generate a high definition neural image of manipulated objects. Active touching, or haptics, involves the interpretation of complex spatiotemporal patterns of stimuli that are likely to activate many classes of mechanoreceptors. Indeed, manipulating an object with the hand can often provide enough information to identify the object, a capacity called stereognosis. By recording the responses of individual sensory afferents in the nerves of humans and non human primates, it has been possible to characterize the responses of these afferents under controlled conditions and gain insights into their contribution to somatic sensation. Here we consider four distinct classes of mechanoreceptive afferents that innervate the glabrous skin of the hand (Figure 9.5A; Table 9.2), as well as those that innervate the hair follicles in hairy skin (Figure 9.5B). An important aspect of the neurological assessment involves testing the functions of these different classes of mechanoreceptive afferents and noting geographically constrained zones, called dermatomes, that may present sensory loss in patients with nerve or spinal cord injury (Clinical Applications).

گیرندههای مکانیکی متخصص در دریافت اطلاعات لمسی

درک ما از سهم مسیرهای آوران متمایز در حس پوستی، به بهترین شکل در بخشهای بدون مو (بدون کرک) دست (یعنی کف دست و نوک انگشتان) توسعه یافته است. این مناطق از سطح پوست برای ایجاد یک تصویر عصبی با کیفیت بالا از اشیاء دستکاری شده تخصص یافتهاند. لمس فعال یا هاپتیک، شامل تفسیر الگوهای پیچیده مکانی-زمانی محرکهایی است که احتمالاً بسیاری از طبقات گیرندههای مکانیکی را فعال میکنند. در واقع، دستکاری یک شیء با دست اغلب میتواند اطلاعات کافی برای شناسایی شیء فراهم کند، ظرفیتی که استریوگنوز نامیده میشود. با ثبت پاسخهای آورانهای حسی منفرد در اعصاب انسانها و نخستیسانان غیرانسانی، میتوان پاسخهای این آورانها را در شرایط کنترلشده مشخص کرد و به بینشهایی در مورد سهم آنها در حس بدنی دست یافت. در اینجا ما چهار دسته مجزا از آورانهای گیرنده مکانیکی را که پوست بدون کرک دست را عصبدهی میکنند (شکل 9.5A؛ جدول 9.2) و همچنین آنهایی را که فولیکولهای مو را در پوست مودار عصبدهی میکنند (شکل 9.5B) در نظر میگیریم. یک جنبه مهم از ارزیابی عصبی شامل آزمایش عملکرد این دستههای مختلف آورانهای گیرنده مکانیکی و توجه به مناطق جغرافیایی محدود، به نام درماتومها، است که ممکن است در بیماران مبتلا به آسیب عصبی یا نخاعی، باعث از دست دادن حس شوند (کاربردهای بالینی).

FIGURE 9.5 The skin harbors a variety of morphologically distinct mechanoreceptors. (A) This diagram represents the smooth, hairless (glabrous) skin of the fingertip. Table 9.2 summarizes the major characteristics of the various receptor types found in glabrous skin. (B) In hairy skin, tactile stimuli are transduced through a variety of mechanosensory afferents innervating different types of hair follicles. These arrangements are best known in mouse skin (illustrated here); see text for details. Similar mechanosensory afferents are believed to innervate hair follicles in human skin. (A after Johansson and Vallbo, 1983; B from Abraira and Ginty, 2013.)

شکل ۹.۵ پوست انواع گیرندههای مکانیکی متمایز از نظر مورفولوژیکی را در خود جای داده است. (الف) این نمودار پوست صاف و بدون مو (بدون کرک) نوک انگشت را نشان میدهد. جدول ۹.۲ ویژگیهای اصلی انواع مختلف گیرندههای موجود در پوست بدون کرک را خلاصه میکند. (ب) در پوست مودار، محرکهای لمسی از طریق انواع آورانهای حسگرهای مکانیکی که انواع مختلف فولیکولهای مو را عصبدهی میکنند، منتقل میشوند. این ترتیبات در پوست موش (که در اینجا نشان داده شده است) بیشتر شناخته شده است. برای جزئیات به متن مراجعه کنید. اعتقاد بر این است که آورانهای حسگرهای مکانیکی مشابه، فولیکولهای مو را در پوست انسان عصبدهی میکنند. (الف برگرفته از یوهانسون و والبو، ۱۹۸۳؛ ب برگرفته از آبرایرا و گینتی، ۲۰۱۳.)

TABLE 9.2 Afferent Systems and Their Properties

جدول ۹.۲ سیستمهای آوران و ویژگیهای آنها

a Receptive field areas as measured with rapid 0.5 mm indentation. (After K. O. Johnson, 2002.)

a سطح میدان پذیرنده با فرورفتگی سریع ۰.۵ میلیمتری اندازهگیری شد. (به نقل از K. O. Johnson، ۲۰۰۲.)

Merkel cell afferents are slowly adapting fibers that account for about 25% of the mechanosensory afferents in the hand. They are especially enriched in the fingertips, and are the only afferents to sample information from receptor cells located in the epidermis. Merkel cell neurite complexes lie in the tips of the primary epidermal ridges extensions of the epidermis into the underlying dermis that coincide with the prominent ridges (“fingerprints”) on the finger surface. Both Merkel cells and their innervating sensory afferents express the mechanotransduction channel Piezo2. As a result, Merkel cells and their afferent axons can sense mechanical stimuli. Deleting Piezo2 selectively in Merkel cells significantly reduces the sustained and static firing of the innervating afferents. Thus, Merkel cells signal the static aspect of a touch stimulus, such as pressure, whereas the terminal portions of the Merkel afferents in these complexes transduce the dynamic aspects of stimuli. The slowly adapting character of the Merkel cell neurite complexes depends on mechanotransduction. Merkel cells also play an active role in modulating the activity of their afferent axons by releasing neuropeptides on the neurites at junctions that resemble synapses, with the exocytosis of electrondense secretory granules (see Chapter 6). Merkel cell afferents have the highest spatial resolution of all the sensory afferents individual Merkel afferents can resolve spatial details of 0.5 mm. They are also highly sensitive to points, edges, and curvature, which makes them ideally suited for processing information about shape and texture.

آورانهای سلول مرکل، فیبرهای به آرامی سازگارشوندهای هستند که حدود ۲۵٪ از آورانهای حسگرهای مکانیکی دست را تشکیل میدهند. آنها به ویژه در نوک انگشتان غنی شدهاند و تنها آورانهایی هستند که اطلاعات را از سلولهای گیرنده واقع در اپیدرم نمونهبرداری میکنند. کمپلکسهای نوریت سلول مرکل در نوک برآمدگیهای اولیه اپیدرمی – امتدادهای اپیدرم به درم زیرین که با برآمدگیهای برجسته (“اثر انگشت”) روی سطح انگشت همزمان هستند – قرار دارند. هم سلولهای مرکل و هم آورانهای حسی عصبدهنده آنها، کانال انتقال مکانیکی Piezo2 را بیان میکنند. در نتیجه، سلولهای مرکل و آکسونهای آوران آنها میتوانند محرکهای مکانیکی را حس کنند. حذف انتخابی Piezo2 در سلولهای مرکل، شلیک پایدار و ایستا آورانهای عصبدهنده را به طور قابل توجهی کاهش میدهد. بنابراین، سلولهای مرکل جنبه استاتیک یک محرک لمسی، مانند فشار را نشان میدهند، در حالی که بخشهای انتهایی آورانهای مرکل در این کمپلکسها، جنبههای پویای محرکها را انتقال میدهند. ویژگی سازگاری آهسته کمپلکسهای سلول-نوریت مرکل به انتقال مکانیکی بستگی دارد. سلولهای مرکل همچنین با آزاد کردن نوروپپتیدها روی نوریتها در محلهای اتصال شبیه سیناپسها، با اگزوسیتوز گرانولهای ترشحی متراکم از الکترون (به فصل 6 مراجعه کنید)، نقش فعالی در تعدیل فعالیت آکسونهای آوران خود دارند. آورانهای سلول مرکل بالاترین وضوح مکانی را در بین تمام آورانهای حسی دارند. آورانهای مرکل میتوانند جزئیات مکانی 0.5 میلیمتر را تشخیص دهند. آنها همچنین به نقاط، لبهها و انحنا بسیار حساس هستند، که آنها را برای پردازش اطلاعات در مورد شکل و بافت ایدهآل میکند.

Meissner afferents also express Piezo2. They are rapidly adapting fibers that innervate the skin even more densely than Merkel afferents, accounting for about 40% of the mechanosensory innervation of the human hand. Meissner corpuscles lie in the tips of the dermal papillae adjacent to the primary ridges and closest to the skin surface (see Figure 9.5A). These elongated receptors are formed by a connective tissue capsule that contains a set of flattened lamellar cells derived from Schwann cells and nerve terminals, with the capsule and the lamellar cells suspended from the basal epidermis by collagen fibers. The center of the capsule contains two to six afferent nerve fibers that terminate between and around the lamellar cells, a configuration thought to contribute to the transient response of these afferents to somatic stimulation. With indentation of the skin, the dynamic tension transduced by the collagen fibers provides the transient mechanical force that deforms the corpuscle and triggers generator potentials that may induce a volley of action potentials in the afferent fibers. When the stimulus is removed, the indented skin relaxes and the corpuscle returns to its resting configuration, generating another burst of action potentials. Thus, Meissner afferents display characteristic rapidly adapting, on off responses (see Figure 9.4). Due at least in part to their close proximity to the skin surface, Meissner afferents are more than four times as sensitive to skin deformation as Merkel afferents; however, their receptive fields are larger than those of Merkel afferents, and thus they transmit signals with reduced spatial resolution (see Table 9.2).

آورانهای مایسنر نیز Piezo2 را بیان میکنند. آنها به سرعت در حال تطبیق فیبرهایی هستند که پوست را حتی متراکمتر از آورانهای مرکل عصبدهی میکنند و حدود 40٪ از عصبدهی حسگرهای مکانیکی دست انسان را تشکیل میدهند. اجسام مایسنر در نوک پاپیلای پوستی مجاور برآمدگیهای اولیه و نزدیکترین به سطح پوست قرار دارند (شکل 9.5A را ببینید). این گیرندههای کشیده توسط یک کپسول بافت همبند تشکیل میشوند که شامل مجموعهای از سلولهای لایهای مسطح مشتق شده از سلولهای شوان و پایانههای عصبی است، به طوری که کپسول و سلولهای لایهای توسط الیاف کلاژن از اپیدرم پایه آویزان شدهاند. مرکز کپسول شامل دو تا شش فیبر عصبی آوران است که بین و اطراف سلولهای لایهای خاتمه مییابند، پیکربندیای که تصور میشود در پاسخ گذرای این آورانها به تحریک سوماتیک نقش دارد. با فرورفتگی پوست، کشش دینامیکی که توسط فیبرهای کلاژن منتقل میشود، نیروی مکانیکی گذرا را فراهم میکند که باعث تغییر شکل جسمک شده و پتانسیلهای مولد را فعال میکند که ممکن است رگباری از پتانسیلهای عمل را در فیبرهای آوران القا کند. هنگامی که محرک برداشته میشود، پوست فرورفته شل میشود و جسمک به پیکربندی استراحت خود باز میگردد و موج دیگری از پتانسیلهای عمل را ایجاد میکند. بنابراین، آورانهای مایسنر پاسخهای روشن و خاموش با سازگاری سریع را نشان میدهند (شکل 9.4 را ببینید). آورانهای مایسنر، حداقل تا حدی به دلیل نزدیکی به سطح پوست، بیش از چهار برابر آورانهای مرکل به تغییر شکل پوست حساس هستند. با این حال، میدانهای پذیرنده آنها بزرگتر از آورانهای مرکل است و بنابراین سیگنالها را با وضوح مکانی کمتری منتقل میکنند (به جدول 9.2 مراجعه کنید).

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Dermatomes

Each dorsal root (sensory) ganglion and its associated spinal nerve arises from an iterated series of embryonic tissue masses called somites (see Chapter 22). This fact of development explains the overall segmental arrangement of somatic nerves and the targets they innervate in the adult. The territory innervated by each spinal nerve is called a dermatome. In humans, the cutaneous area of each dermatome has been defined in patients in whom specific dorsal roots were affected (as in herpes zoster, or shingles) or after surgical interruption (for relief of pain or other reasons). Such studies show that dermatomal maps vary among individuals. Moreover, dermatomes overlap substantially, so that injury to an individual dorsal root does not lead to complete loss of sensation in the relevant skin region. The overlap is more extensive for sensations of touch, pressure, and vibration than for pain and temperature. Thus, testing for pain sensation provides a more precise assessment of a segmental nerve injury than does testing for responses to touch, pressure, or vibration. The segmental distribution of proprioceptors, however, does not follow the dermatomal map but is more closely allied with the pattern of muscle innervation. Despite these limitations, knowledge of dermatomes is essential in the clinical evaluation of neurological patients, particularly in determining the level of a spinal lesion.

کاربردهای بالینی

درماتومها

هر گانگلیون ریشه پشتی (حسی) و عصب نخاعی مرتبط با آن از یک سری تکرارشونده از تودههای بافت جنینی به نام سومایتها (به فصل ۲۲ مراجعه کنید) ناشی میشود. این واقعیت تکامل، آرایش کلی سگمنتال اعصاب سوماتیک و اهدافی را که در بزرگسالان عصبدهی میکنند، توضیح میدهد. ناحیهای که توسط هر عصب نخاعی عصبدهی میشود، درماتوم نامیده میشود. در انسان، ناحیه پوستی هر درماتوم در بیمارانی که ریشههای پشتی خاصی در آنها تحت تأثیر قرار گرفته است (مانند هرپس زوستر یا زونا) یا پس از قطع جراحی (برای تسکین درد یا دلایل دیگر) تعریف شده است. چنین مطالعاتی نشان میدهد که نقشههای درماتوم در بین افراد متفاوت است. علاوه بر این، درماتومها به طور قابل توجهی همپوشانی دارند، به طوری که آسیب به یک ریشه پشتی منجر به از دست دادن کامل حس در ناحیه پوستی مربوطه نمیشود. این همپوشانی برای حس لمس، فشار و ارتعاش گستردهتر از درد و دما است. بنابراین، آزمایش حس درد، ارزیابی دقیقتری از آسیب عصبی سگمنتال نسبت به آزمایش پاسخ به لمس، فشار یا ارتعاش ارائه میدهد. با این حال، توزیع سگمنتال گیرندههای عمقی از نقشه پوستی پیروی نمیکند، بلکه با الگوی عصبدهی عضلات ارتباط نزدیکتری دارد. علیرغم این محدودیتها، آگاهی از درماتومها در ارزیابی بالینی بیماران عصبی، به ویژه در تعیین سطح ضایعه نخاعی، ضروری است.

The innervation arising from a single dorsal root ganglion and its spinal nerve is called a dermatome. The full set of sensory dermatomes is shown here for a typical adult. Knowledge of this arrangement is particularly important in defining the location of suspected spinal (and other) lesions. The numbers refer to the spinal segments by which each nerve is named. (A,C after Rosenzweig et al., 2005; Haymaker and Woodhall, 1967: B after Haymaker and Woodhall, 1967.)

عصبدهی ناشی از یک گانگلیون ریشه پشتی و عصب نخاعی آن، درماتوم نامیده میشود. مجموعه کامل درماتومهای حسی در اینجا برای یک بزرگسال معمولی نشان داده شده است. آگاهی از این ترتیب به ویژه در تعیین محل ضایعات مشکوک نخاعی (و سایر ضایعات) مهم است. اعداد به بخشهای نخاعی اشاره دارند که هر عصب با آنها نامگذاری شده است. (A، C به نام Rosenzweig و همکاران، ۲۰۰۵؛ Haymaker و Woodhall، ۱۹۶۷: B به نام Haymaker و Woodhall، ۱۹۶۷.)

Meissner corpuscles are particularly efficient in transducing information about the relatively low frequency vibrations (3-40 Hz) that occur when textured objects are moved across the skin. Several lines of evidence suggest that the information conveyed by Meissner afferents is responsible for detecting slippage between the skin and an object held in the hand, essential feedback information for the efficient control of grip.

اجسام مایسنر به ویژه در انتقال اطلاعات مربوط به ارتعاشات فرکانس نسبتاً پایین (3-40 هرتز) که هنگام حرکت اشیاء بافتدار روی پوست رخ میدهند، کارآمد هستند. شواهد متعددی نشان میدهد که اطلاعات منتقل شده توسط آورانهای مایسنر مسئول تشخیص لغزش بین پوست و جسمی است که در دست نگه داشته میشود، اطلاعات بازخوردی ضروری برای کنترل کارآمد گرفتن.

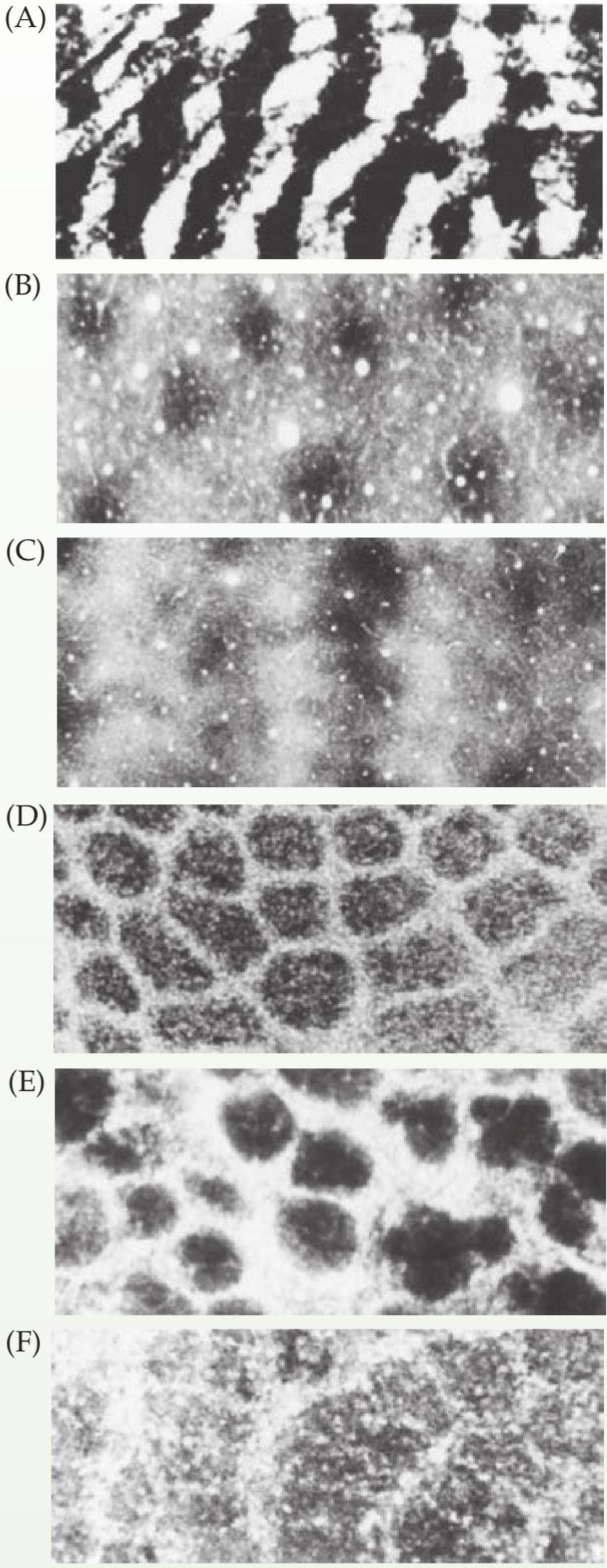

FIGURE 9.6 Simulation of activity patterns in different mechanosensory afferents in the fingertip. Each dot in the response records represents an action potential recorded from a single mechanosensory afferent fiber innervating the human finger as it moves across a row of Braille type. A horizontal line of dots in the raster plot represents the pattern of activity in the afferent as a result of moving the pattern from left to right across the finger. The position of the pattern (relative to the tip of the finger) was then displaced by a small distance, and the pattern was once again moved across the finger. Repeating this pattern multiple times produces a record that simulates the pattern of activity that would arise in a population of afferents whose receptive fields lie along a line in the fingertip (red dots). Only slowly adapting Merkel cell afferents (top panel) provide a highfidelity representation of the Braille pattern that is, the individual Braille dots can be distinguished only in the pattern of Merkel afferent neural activity. (After Phillips et al., 1990.)

شکل ۹.۶ شبیهسازی الگوهای فعالیت در آورانهای حسگرهای مکانیکی مختلف در نوک انگشت. هر نقطه در رکوردهای پاسخ، نشاندهنده یک پتانسیل عمل ثبت شده از یک فیبر آوران حسگرهای مکانیکی است که انگشت انسان را هنگام حرکت در امتداد یک ردیف از نوع بریل، عصبدهی میکند. یک خط افقی از نقاط در نمودار رستری، الگوی فعالیت در آوران را در نتیجه حرکت الگو از چپ به راست در سراسر انگشت نشان میدهد. سپس موقعیت الگو (نسبت به نوک انگشت) با فاصله کمی جابجا شد و الگو بار دیگر در سراسر انگشت حرکت داده شد. تکرار این الگو چندین بار، رکوردی را ایجاد میکند که الگوی فعالیتی را که در جمعیتی از آورانها ایجاد میشود، شبیهسازی میکند. میدانهای پذیرنده آنها در امتداد یک خط در نوک انگشت قرار دارند (نقاط قرمز). تنها آورانهای سلول مرکل که به آرامی تطبیق مییابند (پانل بالا) نمایش با دقت بالایی از الگوی بریل ارائه میدهند، یعنی نقاط بریل منفرد را فقط میتوان در الگوی فعالیت عصبی آوران مرکل تشخیص داد. (بعد از فیلیپس و همکاران، ۱۹۹۰.)

Pacinian afferents are rapidly adapting fibers that make up 10-15% of the mechanosensory innervation in the hand. Pacinian corpuscles are located deep in the dermis or in the subcutaneous tissue; their appearance resembles that of a small onion, with concentric layers of membranes surrounding a single afferent fiber (see Figure 9.5A). This laminar capsule acts as a filter, allowing only transient disturbances at high frequencies (250-350 Hz) to activate the nerve endings. Pacinian corpuscles adapt more rapidly than Meissner corpuscles and have a lower response threshold. The most sensitive Pacinian afferents generate action potentials for displacements of the skin as small as 10 nanometers. Because they are so sensitive, the receptive fields of Pacinian afferents are often large and their boundaries are difficult to define. The properties of Pacinian afferents make them well suited to detect vibrations transmitted through objects that contact the hand or are being grasped in the hand, especially when making or breaking contact. These properties are important for the skilled use of tools (e.g., using a wrench, cutting bread with a knife, writing).

آورانهای پاچینی، فیبرهای سریعالانتقالی هستند که 10 تا 15 درصد از عصبدهی حسگرهای مکانیکی دست را تشکیل میدهند. جسمکهای پاچینی در اعماق درم یا بافت زیر جلدی قرار دارند؛ ظاهر آنها شبیه یک پیاز کوچک است، با لایههای متحدالمرکز غشا که یک فیبر آوران را احاطه کردهاند (شکل 9.5A را ببینید). این کپسول لایهای به عنوان یک فیلتر عمل میکند و فقط به اختلالات گذرا در فرکانسهای بالا (250 تا 350 هرتز) اجازه میدهد تا انتهای عصب را فعال کنند. جسمکهای پاچینی سریعتر از جسمکهای مایسنر سازگار میشوند و آستانه پاسخ پایینتری دارند. حساسترین آورانهای پاچینی، پتانسیلهای عمل برای جابجاییهای پوست به کوچکی 10 نانومتر ایجاد میکنند. از آنجا که آنها بسیار حساس هستند، میدانهای پذیرنده آورانهای پاچینی اغلب بزرگ هستند و تعریف مرزهای آنها دشوار است. خواص آورانهای پاچینی، آنها را برای تشخیص ارتعاشات منتقل شده از طریق اشیایی که با دست تماس پیدا میکنند یا در دست گرفته میشوند، به خصوص هنگام ایجاد یا قطع تماس، بسیار مناسب میکند. این خواص برای استفاده ماهرانه از ابزارها (مثلاً استفاده از آچار، بریدن نان با چاقو، نوشتن) مهم هستند.

Ruffini afferents are slowly adapting fibers and are the least understood of the cutaneous mechanoreceptors. Ruffini endings are elongated, spindle shaped, capsular specializations located deep in the skin, as well as in ligaments and tendons (see Figure 9.5A). The long axis of the corpuscle is usually oriented parallel to the stretch lines in skin; thus, Ruffini corpuscles are particularly sensitive to the cutaneous stretching produced by digit or limb movements; they account for about 20% of the mechanoreceptors in the human hand. Although there is still some question as to their function, Ruffini corpuscles are thought to be especially responsive to skin stretches, such as those that occur during the movement of the fingers. Information supplied by Ruffini afferents contributes, along with muscle receptors, to providing an accurate representation of finger position and the conformation of the hand (see the following section on proprioception).

آورانهای رافینی، فیبرهایی هستند که به آرامی تطبیق مییابند و از میان گیرندههای مکانیکی پوستی، کمتر شناخته شدهاند. انتهای رافینی، رشتههای کپسولی کشیده، دوکی شکل و تخصصی هستند که در اعماق پوست و همچنین در رباطها و تاندونها قرار دارند (شکل 9.5A را ببینید). محور طولی جسمک معمولاً به موازات خطوط کششی پوست جهتگیری میکند. بنابراین، جسمکهای رافینی به طور خاص به کشش پوستی ناشی از حرکات انگشتان یا اندام حساس هستند. آنها حدود 20٪ از گیرندههای مکانیکی دست انسان را تشکیل میدهند. اگرچه هنوز در مورد عملکرد آنها تردیدهایی وجود دارد، اما تصور میشود که جسمکهای رافینی به طور خاص به کششهای پوستی، مانند آنهایی که در حین حرکت انگشتان رخ میدهند، پاسخ میدهند. اطلاعات ارائه شده توسط آورانهای رافینی، همراه با گیرندههای عضلانی، به ارائه نمایش دقیقی از موقعیت انگشت و شکل دست کمک میکند (به بخش بعدی در مورد حس عمقی مراجعه کنید).

The different kinds of information that sensory afferents convey to central structures were first illustrated in experiments conducted by K. O. Johnson and colleagues, who compared the responses of different afferents as a fingertip was moved across a row of raised Braille letters (Figure 9.6). Clearly, all of the afferent types are activated by this stimulation, but the information supplied by each type varies enormously. The pattern of activity in the Merkel afferents is sufficient to recognize the details of the Braille pattern, and the Meissner afferents supply a slightly coarser version of this pattern. But these details are lost in the response of the Pacinian and Ruffini afferents; presumably these responses have more to do with tracking the movement and position of the finger than with the specific identity of the Braille characters. The dominance of Merkel afferents in transducing textural information is probably due to the fact that Braille letters are coarse. Human fingers are also exquisitely sensitive to fine textures. For example, we can easily distinguish silk from satin. The microgeometries of different fine textures produce different patterns of vibrations on the skin while the finger is scanning across the textured surface, which are best detected by the rapidly adapting afferents.

انواع مختلف اطلاعاتی که آورانهای حسی به ساختارهای مرکزی منتقل میکنند، ابتدا در آزمایشهای انجام شده توسط کی. او. جانسون و همکارانش نشان داده شد، که پاسخهای آورانهای مختلف را هنگام حرکت نوک انگشت روی ردیفی از حروف برجسته بریل مقایسه کردند (شکل 9.6). واضح است که همه انواع آورانها توسط این تحریک فعال میشوند، اما اطلاعات ارائه شده توسط هر نوع بسیار متفاوت است. الگوی فعالیت در آورانهای مرکل برای تشخیص جزئیات الگوی بریل کافی است و آورانهای مایسنر نسخه کمی درشتتری از این الگو را ارائه میدهند. اما این جزئیات در پاسخ آورانهای پاسینی و رافینی از بین میروند. احتمالاً این پاسخها بیشتر مربوط به ردیابی حرکت و موقعیت انگشت هستند تا هویت خاص حروف بریل. تسلط آورانهای مرکل در انتقال اطلاعات بافتی احتمالاً به این دلیل است که حروف بریل درشت هستند. انگشتان انسان نیز به بافتهای ظریف بسیار حساس هستند. به عنوان مثال، ما به راحتی میتوانیم ابریشم را از ساتن تشخیص دهیم. ریزهندسههای بافتهای ظریف مختلف، الگوهای ارتعاشی متفاوتی را روی پوست ایجاد میکنند، در حالی که انگشت در حال اسکن کردن سطح بافتدار است، که به بهترین وجه توسط آورانهای سریعاً تطبیقپذیر تشخیص داده میشوند.

Finally, there are also several types of mechanoreceptive afferents that innervate the hair follicles in hairy skin (see Figure 9.5B). These include Merkel cell afferents innervating touch domes associated with the apical collars of hair follicles, and circumferential endings and longitudinal lanceolate endings surrounding the basal regions of the follicles. The longitudinal lanceolate endings form a palisade around the follicle that is exquisitely sensitive to the deflection of the hair by stroking the skin or simply the movement of air over the skin surface. These longitudinal lanceolate endings are derived from Aẞ, A8, or C fibers, all of which form rapidly adapting low threshold mechanoreceptors associated with the hairs. Interestingly, these lanceolate endings appear to be important for mediating forms of sensual touch, such as a gentle caress. These responses of longitudinal lanceolate endings should be distinguished from the responses of free nerve endings in the epidermis, which are also derived from A8 and C axons in peripheral nerves. However, these free nerve endings and the distinct fibers from which they are derived have different physio- logical properties and respond (to painful stimuli) at much higher activation thresholds than touch sensitive receptors associated with hair follicles (see Chapter 10).

در نهایت، چندین نوع آوران گیرنده مکانیکی نیز وجود دارند که فولیکولهای مو را در پوست مودار عصبدهی میکنند (شکل 9.5B را ببینید). این آورانها شامل آورانهای سلول مرکل هستند که گنبدهای لمسی مرتبط با یقههای رأسی فولیکولهای مو و انتهایهای محیطی و نیزهای طولی اطراف نواحی پایه فولیکولها را عصبدهی میکنند. انتهای نیزهای طولی، نردهای را در اطراف فولیکول تشکیل میدهند که به طرز چشمگیری به انحراف مو با نوازش پوست یا صرفاً حرکت هوا روی سطح پوست حساس است. این انتهای نیزهای طولی از فیبرهای Aẞ، A8 یا C مشتق شدهاند که همگی گیرندههای مکانیکی آستانه پایین و به سرعت تطبیقپذیر مرتبط با موها را تشکیل میدهند. جالب توجه است که به نظر میرسد این انتهای نیزهای برای واسطهگری انواع لمس شهوانی، مانند نوازش ملایم، مهم هستند. این پاسخهای انتهای نیزهای طولی را باید از پاسخهای انتهای عصبی آزاد در اپیدرم که آنها نیز از آکسونهای A8 و C در اعصاب محیطی مشتق شدهاند، متمایز کرد. با این حال، این انتهای عصبی آزاد و فیبرهای متمایزی که از آنها مشتق شدهاند، خواص فیزیولوژیکی متفاوتی دارند و (به محرکهای دردناک) در آستانههای فعالسازی بسیار بالاتری نسبت به گیرندههای حساس به لمس مرتبط با فولیکولهای مو پاسخ میدهند (به فصل 10 مراجعه کنید).

Mechanoreceptors Specialized for Proprioception

While cutaneous mechanoreceptors provide information derived from external stimuli, another major class of receptors provides information about mechanical forces arising within the body itself, particularly from the musculoskeletal system. The purpose of these proprioceptors (“receptors for self”) is primarily to give detailed and continuous information about the position of the limbs and other body parts in space. Low-threshold mechanoreceptors, including muscle spindles, Golgi tendon organs, and joint receptors, provide this kind of sensory information, which is essential to the accurate performance of complex movements. Information about the position and motion of the head is particularly important; in this case, proprioceptors are integrated with the highly specialized vestibular system, which we will consider in Chapter 14. (Specialized proprioceptors also exist in the heart and major blood vessels to provide information about blood pressure, but these neurons are considered to be part of the visceral motor system; see Chapter 21.)

گیرندههای مکانیکی تخصصی برای حس عمقی

در حالی که گیرندههای مکانیکی پوستی اطلاعات مشتق شده از محرکهای خارجی را ارائه میدهند، دسته اصلی دیگری از گیرندهها اطلاعاتی در مورد نیروهای مکانیکی ناشی از خود بدن، به ویژه از سیستم اسکلتی-عضلانی، ارائه میدهند. هدف این گیرندههای عمقی (“گیرندههای خود”) در درجه اول ارائه اطلاعات دقیق و مداوم در مورد موقعیت اندامها و سایر قسمتهای بدن در فضا است. گیرندههای مکانیکی با آستانه پایین، از جمله دوکهای عضلانی، اندامهای تاندونی گلژی و گیرندههای مفصلی، این نوع اطلاعات حسی را ارائه میدهند که برای انجام دقیق حرکات پیچیده ضروری است. اطلاعات در مورد موقعیت و حرکت سر به ویژه مهم است. در این مورد، گیرندههای عمقی با سیستم دهلیزی بسیار تخصصی ادغام میشوند که در فصل ۱۴ به آن خواهیم پرداخت. (گیرندههای عمقی تخصصی همچنین در قلب و رگهای خونی اصلی وجود دارند تا اطلاعاتی در مورد فشار خون ارائه دهند، اما این نورونها بخشی از سیستم حرکتی احشایی در نظر گرفته میشوند. به فصل ۲۱ مراجعه کنید.)

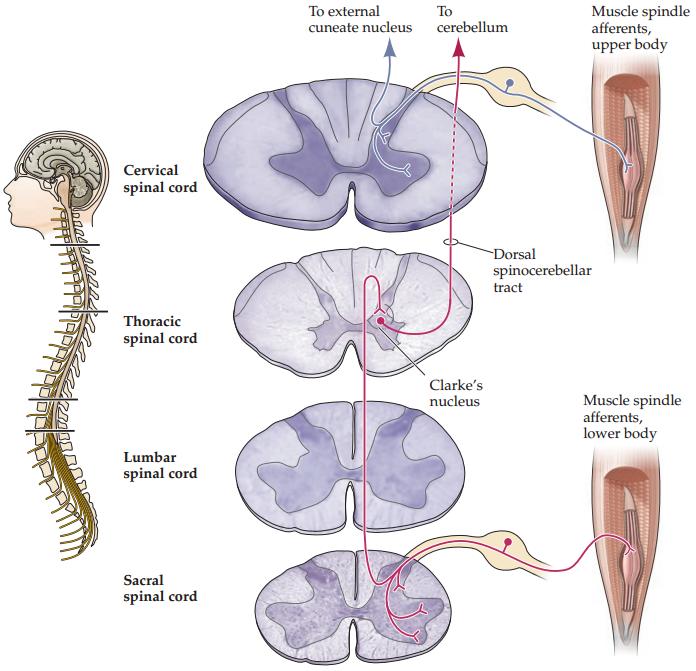

The most detailed knowledge about proprioception derives from studies of muscle spindles, which are found in all but a few striated (skeletal) muscles. Muscle spindles consist of four to eight specialized intrafusal muscle fibers surrounded by a capsule of connective tissue. The intrafusal fibers are distributed among and in a parallel arrangement with the extrafusal fibers of skeletal muscle, which are the true forceproducing fibers (Figure 9.7A). Sensory afferents are coiled around the central part of the intrafusal spindle, and when the muscle is stretched, the tension on the intrafusal fibers activates mechanically gated ion channels in the nerve endings, triggering action potentials. Innervation of the muscle spindle arises from two classes of fibers: primary and secondary endings. Primary endings arise from the largest myelinated sensory axons (group la afferents) and have rapidly adapting responses to changes in muscle length; in contrast, secondary endings (group II afferents) produce sustained responses to constant muscle lengths. Primary endings are thought to transmit information about limb dynamics the velocity and direction of movement whereas secondary endings provide information about the static position of limbs. Piezo2 is expressed by proprioceptors and is required for functional proprioception.

دقیقترین دانش در مورد حس عمقی از مطالعات دوکهای عضلانی حاصل میشود که در همه عضلات مخطط (اسکلتی) به جز تعداد کمی یافت میشوند. دوکهای عضلانی از چهار تا هشت فیبر عضلانی داخل دوکی تخصصی تشکیل شدهاند که توسط کپسولی از بافت همبند احاطه شدهاند. فیبرهای داخل دوکی در بین و به صورت موازی با فیبرهای خارج دوکی عضله اسکلتی، که فیبرهای تولید کننده نیروی واقعی هستند، توزیع شدهاند (شکل 9.7A). آورانهای حسی در اطراف قسمت مرکزی دوک داخل دوکی پیچیده شدهاند و هنگامی که عضله کشیده میشود، تنش روی فیبرهای داخل دوکی، کانالهای یونی دارای دریچه مکانیکی را در انتهای عصب فعال میکند و پتانسیلهای عمل را به راه میاندازد. عصبدهی دوک عضلانی از دو دسته فیبر ناشی میشود: انتهای اولیه و ثانویه. انتهای اولیه از بزرگترین آکسونهای حسی میلیندار (آورانهای گروه la) ناشی میشود و پاسخهای تطبیقی سریعی به تغییرات طول عضله دارند. در مقابل، انتهای ثانویه (آورانهای گروه II) پاسخهای پایدار به طول ثابت عضله ایجاد میکنند. تصور میشود که پایانههای اولیه اطلاعات مربوط به دینامیک اندام، سرعت و جهت حرکت را منتقل میکنند، در حالی که پایانههای ثانویه اطلاعاتی در مورد موقعیت استاتیک اندامها ارائه میدهند. Piezo2 توسط گیرندههای عمقی بیان میشود و برای حس عمقی عملکردی مورد نیاز است.

Changes in muscle length are not the only factors affecting the response of spindle afferents. The intrafusal fibers are themselves contractile muscle fibers and are controlled by a separate set of motor neurons (y motor neurons) in the ventral horn of the spinal cord. Whereas intrafusal fibers do not add appreciably to the force of muscle contraction, changes in the tension of intrafusal fibers have significant impact on the sensitivity of the spindle afferents to changes in muscle length. Thus, in order for central circuits to provide an accurate account of limb position and movement, the level of activity in the y system must be taken into account. (For a more detailed explanation of the interaction of the y system and the activity of spindle afferents, see Chapter 16.)

تغییرات طول عضله تنها عواملی نیستند که بر پاسخ آورانهای دوک عضلانی تأثیر میگذارند. فیبرهای داخل دوکی، خود فیبرهای عضلانی انقباضی هستند و توسط مجموعهای جداگانه از نورونهای حرکتی (نورونهای حرکتی y) در شاخ شکمی نخاع کنترل میشوند. در حالی که فیبرهای داخل دوکی به طور قابل توجهی به نیروی انقباض عضله نمیافزایند، تغییرات در کشش فیبرهای داخل دوکی تأثیر قابل توجهی بر حساسیت آورانهای دوکی به تغییرات طول عضله دارند. بنابراین، برای اینکه مدارهای مرکزی بتوانند گزارش دقیقی از موقعیت و حرکت اندام ارائه دهند، باید سطح فعالیت در سیستم y در نظر گرفته شود. (برای توضیح دقیقتر در مورد تعامل سیستم y و فعالیت آورانهای دوکی، به فصل 16 مراجعه کنید.)

The density of spindles in human muscles varies. Large muscles that generate coarse movements have relatively few spindles; in contrast, extraocular muscles and the intrinsic muscles of the hand and neck are richly supplied with spindles, reflecting the importance of accurate eye movements, the need to manipulate objects with great finesse, and the continuous demand for precise positioning of the head. This relationship between receptor density and muscle size is consistent with the generalization that the sensorimotor apparatus at all levels of the nervous system is much richer for the hands, head, speech organs, and other parts of the body that are used to perform especially important and demanding tasks. Spindles are lacking altogether in a few muscles, such as those of the middle ear, that do not require the kind of feedback that these receptors provide.

تراکم دوکهای عصبی در عضلات انسان متفاوت است. عضلات بزرگی که حرکات خشن ایجاد میکنند، دوکهای عصبی نسبتاً کمی دارند؛ در مقابل، عضلات خارج چشمی و عضلات داخلی دست و گردن به وفور از دوکهای عصبی برخوردارند که نشاندهنده اهمیت حرکات دقیق چشم، نیاز به دستکاری اشیاء با ظرافت زیاد و نیاز مداوم به موقعیتیابی دقیق سر است. این رابطه بین تراکم گیرندهها و اندازه عضلات با این تعمیم سازگار است که دستگاه حسی-حرکتی در تمام سطوح سیستم عصبی برای دستها، سر، اندامهای گفتاری و سایر قسمتهای بدن که برای انجام وظایف بسیار مهم و دشوار استفاده میشوند، بسیار غنیتر است. دوکهای عصبی در چند عضله، مانند عضلات گوش میانی، که به نوع بازخوردی که این گیرندهها ارائه میدهند نیاز ندارند، به طور کلی وجود ندارند.

Whereas muscle spindles are specialized to signal changes in muscle length, low-threshold mechanoreceptors in tendons inform the CNS about changes in muscle tension. These mechanoreceptors, called Golgi tendon organs, are formed by branches of group Ib afferents distributed among the collagen fibers that form the tendons (Figure 9.7B). Each Golgi tendon organ is arranged in series with a small number (10-20) of extrafusal muscle fibers. Taken together, the population of Golgi tendon organs for a given muscle provides an accurate sample of the tension that exists in the muscle.

در حالی که دوکهای عضلانی برای ارسال سیگنال تغییرات در طول عضله تخصص یافتهاند، گیرندههای مکانیکی آستانه پایین در تاندونها، تغییرات در تنش عضلانی را به سیستم عصبی مرکزی (CNS) اطلاع میدهند. این گیرندههای مکانیکی، که اندامهای تاندونی گلژی نامیده میشوند، توسط شاخههایی از آورانهای گروه Ib که در بین فیبرهای کلاژن تشکیلدهنده تاندونها توزیع شدهاند، تشکیل میشوند (شکل 9.7B). هر اندام تاندونی گلژی به صورت سری با تعداد کمی (10-20) فیبر عضلانی خارج دوکی قرار گرفته است. در مجموع، جمعیت اندامهای تاندونی گلژی برای یک عضله مشخص، نمونه دقیقی از تنش موجود در عضله را ارائه میدهد.

How each of these proprioceptive afferents contributes to the perception of limb position, movement, and force remains an area of active investigation. Experiments using vibrators to stimulate the spindles of specific muscles have provided compelling evidence that the activity of these afferents can give rise to vivid sensations of movement in immobilized limbs. For example, vibration of the biceps muscle leads to the illusion that the elbow is moving to an extended position, as if the biceps were being stretched. Similar illusions of motion have been evoked in postural and facial muscles. In some cases, the magnitude of the effect is so great that it produces a percept that is anatomically impossible; for example, when an extensor muscle of the wrist is vigorously vibrated, individuals report that the hand is hyperextended to the point where it is almost in contact with the back of the forearm. In all such cases, the illusion occurs only if the individual is blindfolded and cannot see the position of the limb, demonstrating that even though proprioceptive afferents alone can provide cues about limb position, under normal conditions both somatic and visual cues play important roles.

اینکه چگونه هر یک از این آورانهای حس عمقی در درک موقعیت، حرکت و نیرو اندام نقش دارند، همچنان حوزهای از تحقیقات فعال است. آزمایشهایی که از ویبراتورها برای تحریک دوکهای عضلات خاص استفاده میکنند، شواهد قانعکنندهای ارائه دادهاند که فعالیت این آورانها میتواند باعث ایجاد احساسات واضح حرکت در اندامهای بیحرکت شود. به عنوان مثال، لرزش عضله دوسر بازو منجر به این توهم میشود که آرنج در حال حرکت به حالت کشیده است، گویی عضله دوسر بازو کشیده شده است. توهمات حرکتی مشابهی در عضلات وضعیتی و صورت ایجاد شده است. در برخی موارد، بزرگی اثر آنقدر زیاد است که ادراکی ایجاد میکند که از نظر آناتومیکی غیرممکن است. به عنوان مثال، هنگامی که یک عضله بازکننده مچ دست به شدت ارتعاش مییابد، افراد گزارش میدهند که دست بیش از حد کشیده شده است تا جایی که تقریباً با پشت ساعد در تماس است. در تمام این موارد، این توهم تنها در صورتی رخ میدهد که فرد چشمبند داشته باشد و نتواند موقعیت اندام را ببیند، که نشان میدهد اگرچه آورانهای حس عمقی به تنهایی میتوانند نشانههایی در مورد موقعیت اندام ارائه دهند، در شرایط عادی هم نشانههای جسمی و هم نشانههای بصری نقش مهمی ایفا میکنند.

FIGURE 9.7 Proprioceptors in the musculoskeletal system. These “self receptors” provide information about the position of the limbs and other body parts in space. (A) A muscle spindle and several extrafusal muscle fibers. The specialized intrafusal muscle fibers of the spindle are surrounded by a capsule of connective tissue. (B) Golgi tendon organs are low threshold mechanoreceptors found in tendons; they provide information about changes in muscle tension. (A after Matthews, 1964.)

شکل ۹.۷ گیرندههای عمقی در سیستم اسکلتی-عضلانی. این «گیرندههای خودی» اطلاعاتی در مورد موقعیت اندامها و سایر قسمتهای بدن در فضا ارائه میدهند. (الف) یک دوک عضلانی و چندین فیبر عضلانی خارج دوکی. فیبرهای عضلانی داخل دوکی تخصصی دوک توسط کپسولی از بافت همبند احاطه شدهاند. (ب) اندامهای تاندونی گلژی، گیرندههای مکانیکی آستانه پایین هستند که در تاندونها یافت میشوند. آنها اطلاعاتی در مورد تغییرات تنش عضلانی ارائه میدهند. (الف، برگرفته از متیوز، ۱۹۶۴.)

Prior to these studies, the primary source of proprioceptive information about limb position and movement was thought to arise from mechanoreceptors in and around joints. These joint receptors resemble many of the receptors found in the skin, including Ruffini endings and Pacinian corpuscles. However, individuals who have had artificial joint replacements were found to exhibit only minor deficits in judging the position or motion of limbs, and anesthetizing a joint such as the knee has no effect on judgments of the joint’s position or movement. Although they make little contribution to limb proprioception, joint receptors appear to be important for judging position of the fingers. Along with cutaneous signals from Ruffini afferents and input from muscle spindles that contribute to fine representation of finger position, joint receptors appear to play a protective role in signaling positions that lie near the limits of normal finger joint range of motion.

پیش از این مطالعات، تصور میشد منبع اصلی اطلاعات حس عمقی در مورد موقعیت و حرکت اندام، از گیرندههای مکانیکی داخل و اطراف مفاصل ناشی میشود. این گیرندههای مفصلی شبیه بسیاری از گیرندههای موجود در پوست، از جمله انتهای رافینی و جسمکهای پاچینی هستند. با این حال، مشخص شد افرادی که تعویض مفصل مصنوعی داشتهاند، تنها نقصهای جزئی در قضاوت موقعیت یا حرکت اندامها نشان میدهند و بیحس کردن مفصلی مانند زانو هیچ تأثیری بر قضاوت موقعیت یا حرکت مفصل ندارد. اگرچه آنها سهم کمی در حس عمقی اندام دارند، اما به نظر میرسد گیرندههای مفصلی برای قضاوت موقعیت انگشتان مهم هستند. همراه با سیگنالهای پوستی از آورانهای رافینی و ورودی از دوکهای عضلانی که به نمایش دقیق موقعیت انگشت کمک میکنند، به نظر میرسد گیرندههای مفصلی نقش محافظتی در سیگنالدهی موقعیتهایی که نزدیک به محدوده دامنه حرکتی طبیعی مفصل انگشت قرار دارند، ایفا میکنند.

Central Pathways Conveying Tactile Information from the Body: The Dorsal Column Medial Lemniscal System

The axons of cutaneous mechanosensory afferents enter the spinal cord through the dorsal roots, where they bifurcate into ascending and descending branches. Both branches give off axonal collaterals that project into the gray matter of the spinal cord across several adjacent segments, terminating in the deeper layers (laminae III, IV, and V) in the dorsal horn. The main ascending branches extend ipsilaterally through the dorsal columns (also called the posterior funiculi) of the cord to the lower medulla, where they synapse on neurons in the dorsal column nuclei (Figure 9.8A). The term column refers to the gross columnar appearance of these fibers as they run the length of the spinal cord. These first order neurons (primary sensory neurons) in the pathway can have quite long axonal processes: Neurons innervating the lower extremities, for example, have axons that extend from their peripheral targets through much of the length of the cord to the caudal brainstem. In addition to these socalled direct projections of the first order neurons to the brainstem, projection neurons located in laminae III, IV, and V of the dorsal horn that receive inputs from mechanosensory collaterals project in parallel through the dorsal column to the same dorsal column nuclei. This indirect mechanosensory input to the brainstem is sometimes called the postsynaptic dorsal column projection.

گیرندههای مفصلی مسیرهای مرکزی انتقال اطلاعات لمسی از بدن: ستون پشتی سیستم لمسی میانی

آکسونهای آورانهای حسگرهای مکانیکی پوستی از طریق ریشههای پشتی وارد نخاع میشوند، جایی که به شاخههای صعودی و نزولی تقسیم میشوند. هر دو شاخه، شاخههای جانبی آکسونی را آزاد میکنند که در ماده خاکستری نخاع در چندین بخش مجاور بیرون زده و در لایههای عمیقتر (لامیناهای III، IV و V) در شاخ پشتی خاتمه مییابند. شاخههای صعودی اصلی به صورت همسو از طریق ستونهای پشتی (که به آنها فونیکولهای خلفی نیز گفته میشود) نخاع تا بصلالنخاع تحتانی امتداد مییابند، جایی که روی نورونهای هستههای ستون پشتی سیناپس برقرار میکنند (شکل 9.8A). اصطلاح ستون به ظاهر ستونی ناخالص این فیبرها در طول نخاع اشاره دارد. این نورونهای مرتبه اول (نورونهای حسی اولیه) در مسیر میتوانند زوائد آکسونی نسبتاً طولانی داشته باشند: به عنوان مثال، نورونهایی که اندامهای تحتانی را عصبدهی میکنند، آکسونهایی دارند که از اهداف محیطی خود در طول بخش زیادی از طناب نخاعی تا ساقه مغز دمی امتداد مییابند. علاوه بر این به اصطلاح پروجکشنهای مستقیم نورونهای مرتبه اول به ساقه مغز، نورونهای پروجکشنی واقع در لامینای III، IV و V شاخ پشتی که ورودیهایی از کولترالهای حسگرهای مکانیکی دریافت میکنند، به طور موازی از طریق ستون پشتی به همان هستههای ستون پشتی پروجکت میکنند. این ورودی حسگرهای مکانیکی غیرمستقیم به ساقه مغز گاهی اوقات پروجکشن ستون پشتی پس سیناپسی نامیده میشود.

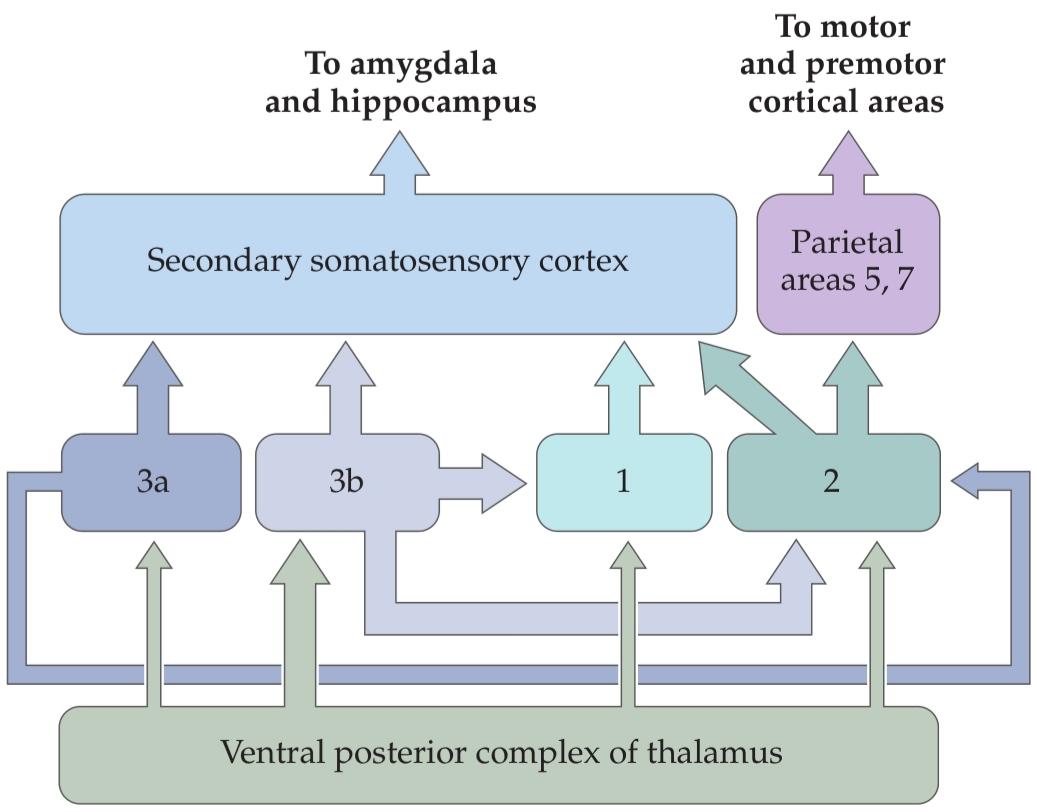

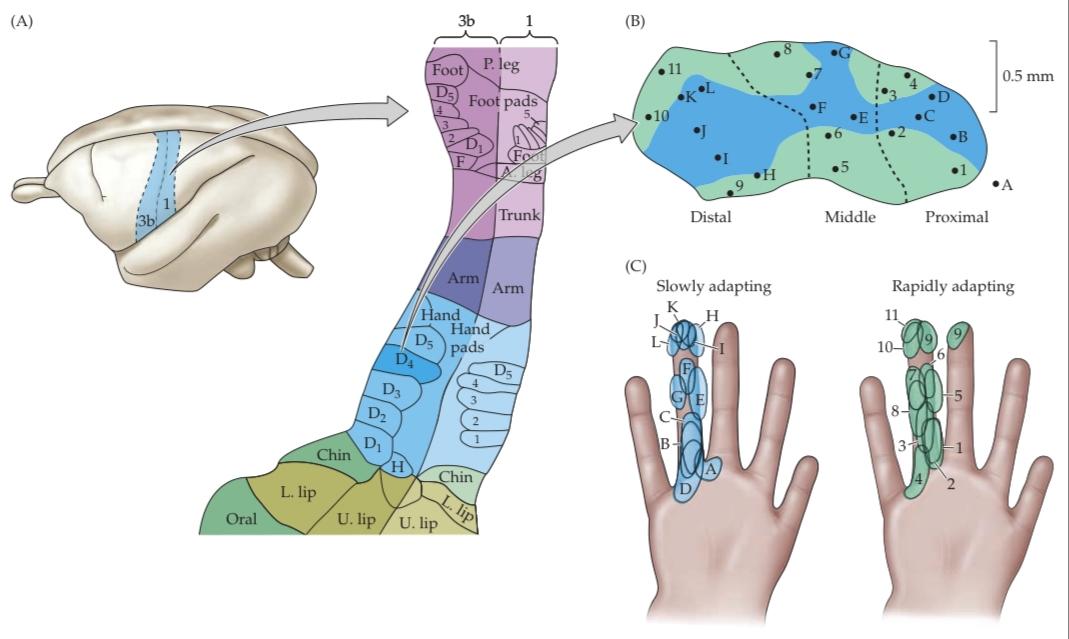

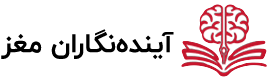

FIGURE 9.8 The main touch pathways. (A) The dorsal column medial lemniscal pathway carries mechanosensory information from the posterior third of the head and the rest of the body. (B) The trigeminal portion of the mechanosensory system carries similar information from the face.

شکل ۹.۸ مسیرهای اصلی لمسی. (الف) مسیر لمسی میانی ستون پشتی، اطلاعات حسگرهای مکانیکی را از یک سوم خلفی سر و بقیه بدن حمل میکند. (ب) بخش سه قلوی سیستم حسگرهای مکانیکی اطلاعات مشابهی را از صورت حمل میکند.

The dorsal columns of the spinal cord are topographically organized such that the fibers conveying information from lower limbs lie most medial and travel in a circumscribed bundle known as the fasciculus gracilis (Latin fasciculus, “bundle”; gracilis, “slender”), or more simply, the gracile tract. Those fibers that convey information from the upper limbs, trunk, and neck lie in a more lateral bundle known as the fasciculus cuneatus (“wedge shaped bundle”) or cuneate tract. In turn, the fibers in these two tracts end in different subdivisions of the dorsal column nuclei: a medial subdivision, the nucleus gracilis or gracile nucleus; and a lateral subdivision, the nucleus cuneatus or cuneate nucleus.

ستونهای پشتی نخاع از نظر توپوگرافی به گونهای سازماندهی شدهاند که فیبرهایی که اطلاعات را از اندامهای تحتانی منتقل میکنند، در قسمت داخلی قرار دارند و در یک دسته محدود به نام fasciculus gracilis (لاتین fasciculus، “دسته”؛ gracilis، “باریک”) یا به عبارت سادهتر، مسیر گراسیل حرکت میکنند. فیبرهایی که اطلاعات را از اندامهای فوقانی، تنه و گردن منتقل میکنند، در یک دسته جانبیتر به نام fasciculus cuneatus (“دسته گوهای شکل”) یا مسیر کونئات قرار دارند. به نوبه خود، فیبرهای این دو مسیر به زیربخشهای مختلف هستههای ستون پشتی ختم میشوند: یک زیربخش داخلی، هسته گراسیلیس یا هسته گراسیل؛ و یک زیربخش جانبی، هسته کونئاتوس یا هسته کونئات.

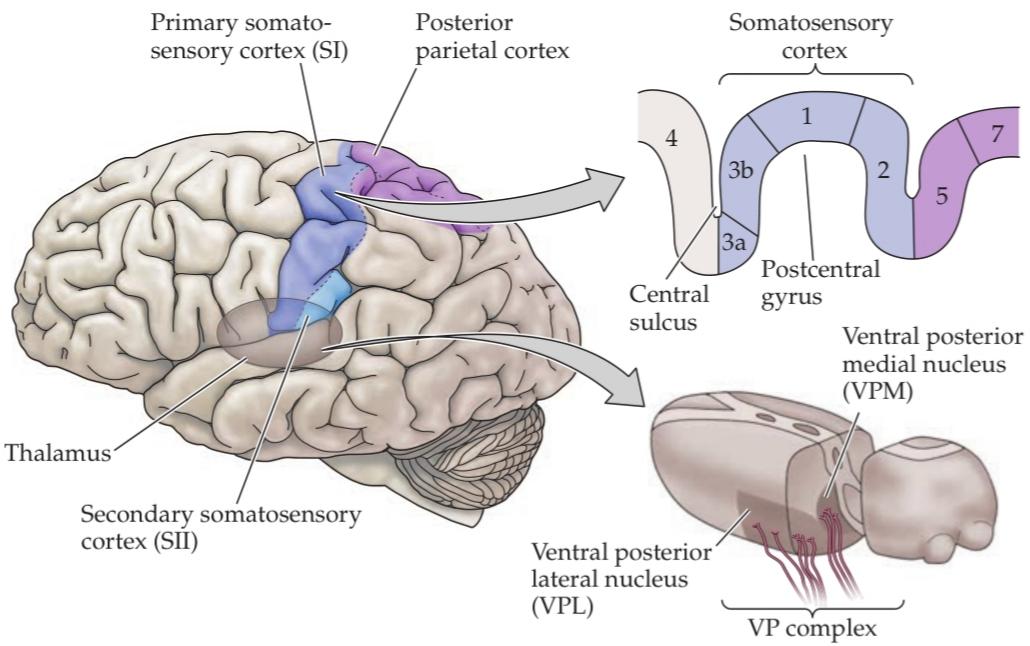

The second-order neurons in the dorsal column nuclei send their axons to the somatosensory portion of the thalamus. The axons exiting from dorsal column nuclei are identified as the internal arcuate fibers. The internal arcuate fibers subsequently cross the midline and then form a dorsoventrally elongated tract known as the medial lemniscus. The word lemniscus means “ribbon”; the crossing of the internal arcuate fibers is called the decussation of the medial lemniscus, from the Roman numeral X, or decem (10). In a cross section through the medulla, such as the one shown in Figure 9.8A, the medial lemniscal axons carrying information from the lower limbs are located ventrally, whereas the axons related to the upper limbs are located dorsally. As the medial lemniscus ascends through the pons and midbrain, it rotates 90 degrees laterally, so that the fibers representing the upper body are eventually located in the medial portion of the tract and those representing the lower body are in the lateral portion. The axons of the medial lemniscus syn- apse with thalamic neurons located in the ventral posterior lateral nucleus (VPL). Thus, the VPL receives input from contralateral dorsal column nuclei.

نورونهای رده دوم در هستههای ستون پشتی، آکسونهای خود را به بخش حسی-پیکری تالاموس میفرستند. آکسونهایی که از هستههای ستون پشتی خارج میشوند، به عنوان فیبرهای قوسی داخلی شناخته میشوند. فیبرهای قوسی داخلی متعاقباً از خط وسط عبور میکنند و یک مسیر کشیده شده به سمت پشت و شکم را تشکیل میدهند که به عنوان لمنیسکوس داخلی شناخته میشود. کلمه لمنیسکوس به معنای “روبان” است؛ تقاطع فیبرهای قوسی داخلی، تقاطع لمنیسکوس داخلی نامیده میشود که از عدد رومی X یا decem گرفته شده است (10). در یک برش عرضی از بصل النخاع، مانند آنچه در شکل 9.8A نشان داده شده است، آکسونهای لمنیسکوس داخلی که اطلاعات را از اندامهای تحتانی حمل میکنند، در قسمت شکمی قرار دارند، در حالی که آکسونهای مربوط به اندامهای فوقانی در قسمت پشتی قرار دارند. همانطور که لمنیسکوس داخلی از طریق پل مغزی و مغز میانی بالا میرود، ۹۰ درجه به صورت جانبی میچرخد، به طوری که الیافی که نمایانگر قسمت فوقانی بدن هستند، در نهایت در قسمت داخلی راه نخاعی و الیافی که نمایانگر قسمت تحتانی بدن هستند در قسمت جانبی قرار میگیرند. آکسونهای لمنیسکوس داخلی با نورونهای تالاموس واقع در هسته جانبی خلفی شکمی (VPL) سیناپس میکنند. بنابراین، VPL ورودی را از هستههای ستون پشتی طرف مقابل دریافت میکند.

Third order neurons in the VPL send their axons via the internal capsule to terminate in the ipsilateral postcentral gyrus of the cerebral cortex, a region known as the primary somatosensory cortex, or SI. Neurons in the VPL also send axons to the secondary somatosensory cortex (SII), a smaller region that lies in the upper bank of the lateral sulcus. Thus, the somatosensory cortex represents mechanosensory signals first generated in the cutaneous surfaces of the contralateral body.

نورونهای رده سوم در VPL، آکسونهای خود را از طریق کپسول داخلی به شکنج پسمرکزی همان طرف قشر مغز، ناحیهای که به عنوان قشر حسی-پیکری اولیه یا SI شناخته میشود، میفرستند. نورونهای VPL همچنین آکسونها را به قشر حسی-پیکری ثانویه (SII)، ناحیه کوچکتری که در قسمت بالایی شیار جانبی قرار دارد، میفرستند. بنابراین، قشر حسی-پیکری نشاندهنده سیگنالهای حسگرهای مکانیکی است که ابتدا در سطوح پوستی بدن طرف مقابل تولید میشوند.

Central Pathways Conveying Tactile Information from the Face: The Trigeminothalamic System

Cutaneous mechanoreceptor information from the face is conveyed centrally by a separate set of first order neurons that are located in the trigeminal (cranial nerve V) ganglion (Figure 9.8B). The peripheral processes of these neurons form the three main subdivisions of the trigeminal nerve (the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular branches). Each branch innervates a well defined territory on the face and head, including the teeth and the mucosa of the oral and nasal cavities. The central processes of trigeminal ganglion cells form the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve; they enter the brainstem at the level of the pons to terminate on neurons in the trigeminal brainstem complex.

مسیرهای مرکزی انتقال اطلاعات لمسی از صورت: سیستم تریژمینوتالامیک

اطلاعات گیرندههای مکانیکی پوستی از صورت به صورت مرکزی توسط مجموعهای جداگانه از نورونهای رده اول که در گانگلیون تریژمینال (عصب جمجمهای V) قرار دارند، منتقل میشوند (شکل 9.8B). زوائد محیطی این نورونها، سه زیرشاخه اصلی عصب تریژمینال (شاخههای چشمی، فکی و فکی) را تشکیل میدهند. هر شاخه، ناحیهای کاملاً مشخص را در صورت و سر، از جمله دندانها و مخاط حفرههای دهان و بینی، عصبدهی میکند. زوائد مرکزی سلولهای گانگلیون تریژمینال، ریشههای حسی عصب تریژمینال را تشکیل میدهند. آنها در سطح پل مغزی وارد ساقه مغز میشوند تا به نورونهای موجود در کمپلکس ساقه مغز تریژمینال ختم شوند.

The trigeminal complex has two major components: the and the spinal nucleus. (A third component, the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus, is considered below.) Most of the afferents conveying information from low threshold cutaneous mechanoreceptors terminate in the principal nucleus. In effect, this nucleus corresponds to the dorsal column nuclei that relay mechanosensory information from the rest of the body. The spinal nucleus contains several subnuclei, and all of them receive inputs from collaterals of mechanoreceptors. Trigeminal neurons that are sensitive to pain, temperature, and non discriminative touch do not project to the principal nucleus; they project to the spinal nucleus of the trigeminal complex (discussed more fully in Chapter 10). The second order neurons of the trigeminal brainstem nuclei give off axons that cross the midline and ascend to the ventral posterior medial (VPM) nucleus of the thalamus by way of the trigeminal lemniscus. Neurons in the VPM send their axons to ipsilateral cortical areas SI and SII.